601

ARTICLE

Journal of Sport Management, 2015, 29, 601 -618

http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/JSM.2014-0296

© 2015 Human Kinetics, Inc.

Gashaw Abeza is with the School of Human Kinetics, University

of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Norm O’Reilly is with

the Department of Sports Administration, College of Business,

Ohio University, Athens, Ohio. Benoit Séguin is with the School

of Human Kinetics, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario,

Canada. Ornella Nzindukiyimana is with Western University,

London, Ontario, Canada. Address author correspondence to

Norm O’Reilly at [email protected].

Social Media Scholarship in Sport Management Research:

A Critical Review

Gashaw Abeza

University of Ottawa

Norm O’Reilly

Ohio University

Benoit Séguin

University of Ottawa

Ornella Nzindukiyimana

Western University

This work critically assesses the history and current state of social media scholarship in sport management

research. Methodologically, the study is based on a comprehensive census review of the current body of

literature in the area of social media. The review identies 123 social media articles in sport management

research that were mined from a cross-disciplinary examination of 29 scholarly journals from January 2008

(earliest found) to June 2014. The work identies the topic areas, the platforms, the theories, and the research

methods that have received the (most/least) attention of the social media research community, and provides

suggestions for future research.

In today’s fast-paced technologically driven world,

social media platforms are rapidly and constantly evolv-

ing in their scope and extent of use, signicantly affect-

ing everyday lives of people across the globe (Rowe &

Hutchins, 2014). This transformation is noticeable in the

global sporting culture, where the scope, penetration, and

magnitude of social media reach has been tremendous

(Pedersen, 2014). Although the development of social

media is still unfolding, its popularity and acceptance

by athletes, coaches, managers, teams, leagues, fans,

events, and sport governing bodies is widespread

(Hutchins, 2014). In light of its growing complexity and

increasing omnipresence, social and behavioral scientists

are intrigued by the dynamics of the interrelationship

between sport and social media (Hutchins, 2014; Ped-

ersen, 2014). Though the scholarship is still relatively

recent (Billings & Hardin, 2014), scholars are examining

social media in various sport settings and gaining insights

into its manifestations, characteristics, usage trends, and

so on. Indeed, a range of research topics associated with

social media have been investigated in diverse elds of

sport management research (Pedersen, 2013), including

sport communication, sport events management, sport

marketing, sport law, and sport governance.

While published research is growing signicantly

(Pedersen, 2014), there is a lack of formal articulation

and an absence of empirical evidence on the current state

and historical evolution of the social media scholarship in

sport management research. Hence, this study attempted

to ll the gap by examining the body of knowledge (i.e.,

research areas, theories, and methods) and historical

trends (i.e., chronological changes in research focus/

interest) of the social media scholarship in sport man-

agement research. The following four research questions

guided this study: (i) what social media topic areas have

received attention in sport management research?; (ii)

which social media platforms have received the (most/

least) attention in sport management research?; (iii) what

theories have been used, advanced, and developed in

social media scholarship in sport management research?;

and (iv) what is the prevalence and the nature of research

methods employed in social media scholarship in sport

management research?

602 Abeza et al.

JSM Vol. 29, No. 6, 2015

In conducting a comprehensive critical self-exam-

ination of the current state and historical evolution of a

scholarship, a research community is able to document

and identify research advancements (Abeza, O’Reilly, &

Nadeau, 2014), gain insight into what the research com-

munity has, and has not, studied (Costa, 2005), and reveal

strengths and areas in need of improvements (Pitts, 2001).

Such self-reective studies have the benets of clarify-

ing assumptions (Chalip, 2006; Costa, 2005), informing

journal editors about increasing attention to areas with

little or no research coverage, and guiding scholars in

locating research (Abeza et al., 2014). In that way, these

studies contribute to shaping future directions for the

scholarship, thus playing a part in the advancement of

scholarly inquiry (Chalip, 2006; Costa, 2005).

Background and Overview

of the Literature

Social media takes many different forms, and popular

examples include social networking sites such as Face-

book, Twitter, Google+, and Tumblr; content-sharing sites

such as YouTube, Flickr, Pinterest, and Instagram; and

blogs. The term social media means various things to dif-

ferent people (McNary & Hardin, 2013). As Kaplan and

Haenlein (2010) explained, there is a limited understand-

ing of what the term precisely means; the term still has

no universally agreed-upon academic denition (Abeza,

O’Reilly, & Reid, 2013). Nevertheless, most denitions

can be encompassed under the denition provided by

Kaplan and Haenlein (2010): “A group of Internet-based

applications that build on the ideological and technologi-

cal foundations of Web 2.0, and that allow the creation

and exchange of User Generated Content” (p. 61).

The term Web 2.0 is also used interchangeably

with the term social media in most literature (Askool

& Nakata, 2011), although the two are not entirely the

same. The term Web 2.0 refers to the technologies used

to enable and facilitate online platforms on which col-

laborative and user-friendly social media communications

occur. The ve major types of Web 2.0 technologies are

blogs, social networks, content communities, forums and

bulletin boards, and content aggregators (Constantinides

& Fountain, 2008). Web 2.0 is considered a derivative

of the original Web (i.e., Internet websites, Web 1.0),

which largely carries a one-way message supplied by

publishers on a static page (Drury, 2008). Web 2.0 refers

to the second generation of Internet-based applications

(Miller & Lammas, 2010), reecting the fact that users

are not passive viewers anymore, and content is no longer

generated only by an individual publisher. Instead, users

engage in participatory and collaborative content genera-

tion (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010). In Web 2.0, social media

users are all involved in sharing, linking, collaborating,

and producing online content using text, photo, audio, and

video (Mangold & Faulds, 2009). Yet, for many, the term

Web 2.0 is a catchall term for a few well-known sites such

as Facebook, YouTube, Flickr, and Twitter. For others

(e.g., Constantinides & Fountain, 2008), the denition

is broader and includes Web 2.0-enabled blogs, and for

a few others still (e.g., Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010, 2012),

it includes collaborative projects (e.g., Wikipedia) and

gaming applications (e.g., World of Warcraft).

A related term that requires clarication is new

media, a catchall phrase used for a range of applications

from the Internet and e-commerce to the Blogosphere,

video games, and virtual reality (Leonard, 2009). It is

commonly used in relation to “old” media forms (e.g.,

print newspapers and magazines), and includes stream-

ing audio and video, e-mail and chat rooms, DVD and

CD-ROM, and integration of digital data with the tele-

phone (e.g., mobile phone, Internet, digital cameras)

(Lievrouw, 2014). New media is broader than social

media, and social media is one segment of the new media.

In this work, social media is considered to be a part of the

social aspects of Web 2.0 applications including, but not

limited to, users’ participation, openness, conversation,

community, and connectedness.

Social Media Scholarship

in Sport Management Research

The eld of sport management captures a variety of

subdisciplines and is studied in a wide variety of con-

texts (Doherty, 2013; Pitts, 2001). The eld includes

subdisciplines such as sport marketing, nance, legal

aspects, governance, communication, organizational

behavior and theory, sport for development, tourism,

facility management, and event management (Andrew,

Pedersen, & McEvoy, 2011; Doherty, 2013; Pitts, 2001).

Social media is, by nature, a communication platform,

and the preponderance of studies on the topic have been

conducted within the subdisciplines of sport communica-

tion (e.g., Emmons & Butler, 2013; Sanderson, 2013) and

sport marketing (e.g., Walsh, Clavio, Lovell, & Blaszka,

2013; Williams & Chinn, 2010). However, the study of

the dynamic interrelationship between sport and social

media has a cross-disciplinary nature (Pedersen, 2013),

and is studied through the lens of and in the context of

the different subdisciplines of sport management, such

as sport law (e.g., Cornish & Larkin, 2014; Wendt &

Young, 2011), sport governance (e.g., Van Namen, 2011),

organizational management (e.g., Alonso & O’Shea,

2012b), sport, race and gender (e.g., Antunovic & Hardin,

2012; Cleland, 2013), and sport event management (e.g.,

McGillivray, 2014).

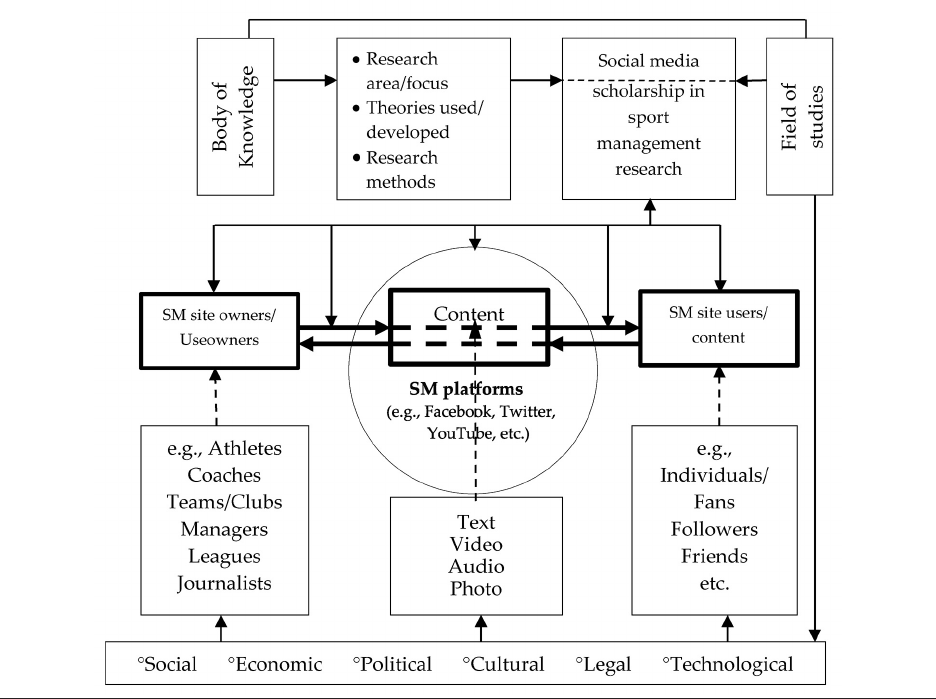

Therefore, taking into consideration the multidisci-

plinary nature of the eld of sport management (Costa,

2005; Doherty, 2013) and the dynamic interrelationship

between sport and social media (Hutchins, 2014; Peder-

sen, 2014), a conceptual framework (see Figure 1) was

constructed. The framework outlines the “big picture”

of the social media scholarship in sport management

research by connecting and compartmentalizing the inter-

relationships among the different segments, contexts, and

areas of sport management research. It is believed that the

Social Media Scholarship in Sport Management Research 603

JSM Vol. 29, No. 6, 2015

framework helps to chart the historical trends, navigate

the body of knowledge of social media scholarship, and

overall, helps to comprehend the scholarship in a more

simplied manner. As depicted in the framework, the

study of the dynamic interrelationship between sport

and social media has a cross-disciplinary nature where

the useowners (e.g., athletes, teams, league, journal-

ists) communicate content (i.e., text, audio, video, and

pictures) to achieve their individual objectives by con-

necting to audiences/social media users (e.g., fans and

individual users—friends and followers) on various Web

2.0 platforms (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, YouTube), and

vice versa. We use the term useowner to differentiate a

corporation that owns the social media platform (e.g.,

Twitter Inc.) from the owner of a social media site who

has control of its use (e.g., @KingJames, LeBron James’

Twitter account).

This interrelationship has an overarching societal,

cultural, economic, political, and technological impact

on today’s society and, in the case of our area of study,

the contemporary sport industry. Hence, the parts, reach,

scope, and landscape of the study of social media can

be visualized—and by extension, its scholarship can

be examined—through the lenses of its segments (i.e.,

useowners, content, prosumers), contexts (i.e., social,

political, economic, political, technological aspects), and

eld of studies (e.g., sport communication, sport market-

ing, sport events management, sport governance, sport

law). Guided by this conceptual framework, we sought

to produce empirical evidence on the trends and state of

the body of knowledge of the social media scholarship

in sport management research.

Method

Data Collection

A cross-disciplinary census review of the social media

academic literature published in sport management jour-

nals from 2008 (the earliest found) to June 2014 was con-

ducted. Five sport-related online search databases were

used, including Academic Search (Ebsco Publishing),

Google Scholar, Scopus (Elsevier), SportDiscus (SIRC),

and Web of Science (Thomson Reuters). The search for

journal articles was based on 12 keyword descriptors:

Figure 1 — A guiding framework in examining the social media (SM) scholarship in sport management research.

604 Abeza et al.

JSM Vol. 29, No. 6, 2015

social media, Web 2.0, new media, online, internet,

social network sites, Facebook, Twitter, 140 characters,

Blog, YouTube, and message boards. The keywords were

identied through brainstorming and a concept map, and

the use of truncation variant words. Synonyms (e.g., new

media, digital media), plural/singular forms (e.g., social

network, social networks), spelling variations (e.g., blog,

Weblog), and acronyms (e.g., SM for “social media”)

were used. The databases were queried for the keywords

in the title, abstract and the keyword list. In addition,

a search was conducted on 30 select journals in sport

management as identied by Andrew et al. (2011). In

total, 123 social media articles were identied, of which

96 were empirical research papers (this count excludes

interviews) sourced from 29 journals. We also excluded

commentaries except for two landmark commentaries that

have inuenced the scholarship (based on the number of

citations they received in successive articles): Leonard

(2009) and Williams and Chinn (2010).

While other publications provide a great deal of

information (e.g., practitioner publications and reports,

textbooks and edited volumes, master’s and doctoral

dissertations, conference papers), they were not selected

for inclusion, as only peer-reviewed academic journals

were considered. Scholarly journals are believed to be the

prime locations where knowledge is constantly updated,

tested, and challenged (Mumby & Stohl, 1996), and col-

lectively stored and disseminated (Rooney, McKenna, &

Barker, 2011).

Data Analysis

Two researchers/coders independently carried out the

classication of the identied research streams, research

methods, platforms, and theories of the 96 empirical

research articles. A codebook and denitions were devel-

oped to help guide the process and a pilot undertaken.

Both an inductive approach (in coding the research

streams) and a deductive approach (in coding the plat-

forms, theories, and methods) were used.

Inductive Approach. The two coders conducted an

independent pilot coding on 18 randomly selected sample

articles, three from each of six author-selected topic areas

in social media and sport management, namely, crisis

communication, legal issues, tool of marketing, consumer

behavior, social issues, and journalism. The emergent

streams from the pilot were compared, and differences

were discussed until an agreement was reached and an

adjustment made. Next, the two coders independently

read through the full length of each of the 96 articles and

conducted the classication of the identied research

streams. In the coding process, the topics addressed in

the research streams are interrelated and some of the

articles, at times, address several topics, meaning that

they may fall into two or more of the research streams.

Given this and per Cornwell and Maignan (1998), the

two coders discussed their coding and the articles were

assigned to a stream based on their main emphasis or

principal contribution. Upon completion of the coding,

one coder identied 16 streams and the other one 11

streams, which were later discussed and agreed upon to

be grouped as streams and substreams (e.g., the stream

= dening constructs; substreams = dimensions of use,

constructs of acceptance, platforms attribute). The two

researchers’ agreement scores ranged from 87% to 91%

on the six research streams.

Deductive Approach. The coding sheet for the

platforms, theories, and methods was developed through

a deductive process by first identifying a working

denition for each item. For example, the codebook used

for the method section was developed by identifying the

commonly used denitions of qualitative, quantitative,

mixed methods and multimethods from the work of

Creswell (2014). Two independent coders conducted

a pilot test of the reliability of the coding sheet. An

intercoder reliability analysis using the kappa statistic

was performed (per Neuendorf, 2002) that determined

consistency among raters on each of platforms (κ =

.807), theories (κ =.846), and methods (κ = .943). These

scores indicate an acceptable level of intercoder reliability

(i.e., coefcients of .80 or greater (see Lombard, Snyder-

Duch, & Bracken, 2002)). The nal classications were

reviewed by two additional researchers/coders and

revised accordingly.

Results

Topic Areas Covered in Social Media

Scholarship in Sport Management

Research

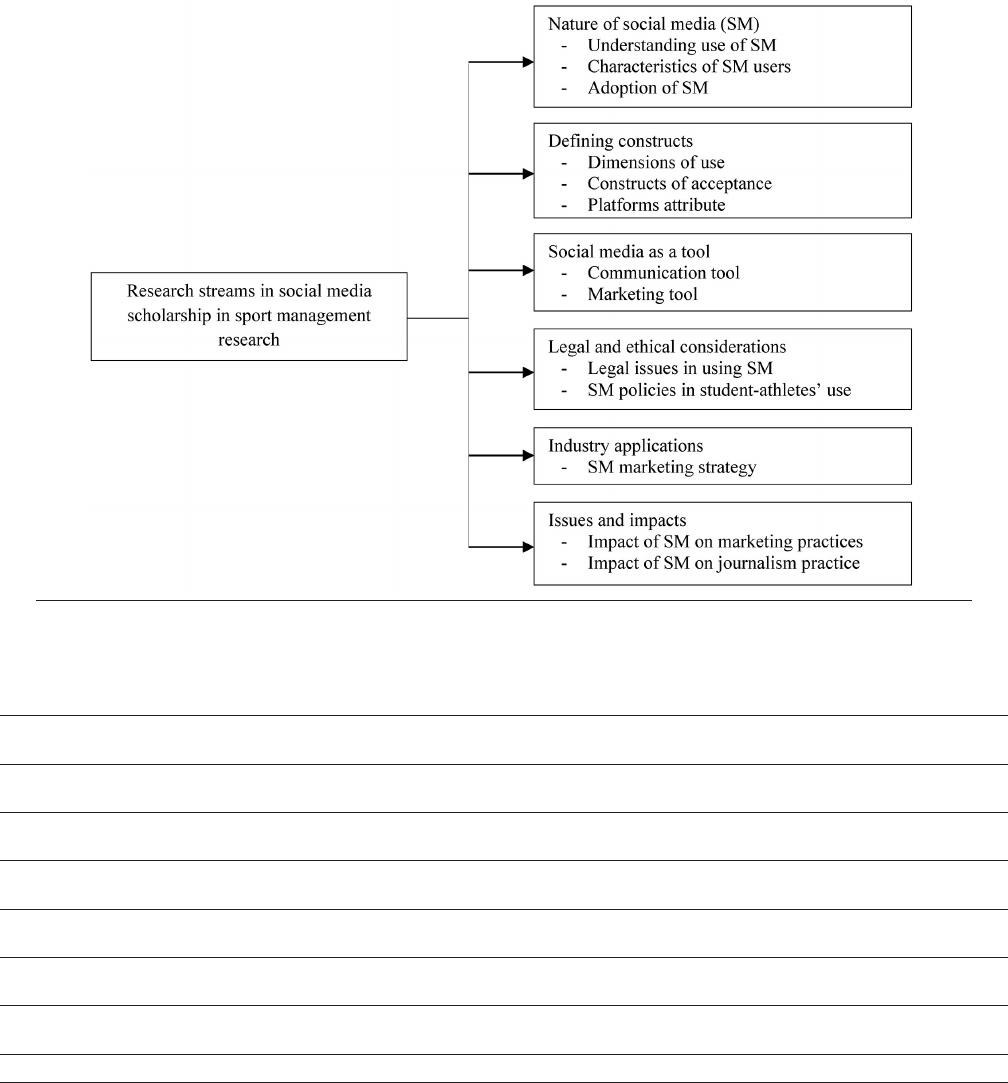

The 96 articles gathered were grouped into one of six

emergent streams of research (see Figure 2), represent-

ing the topics most commonly addressed in the related

literature. Some of the streams are relatively developed

with a considerable body of knowledge, whereas others

consist of only a few studies. The streams include nature

of social media, dening constructs, social media sites

as tools, legal and ethical considerations, industry appli-

cations, and issues and impacts. They are based on the

ndings reported in these studies. Appendix Table 1

lists the 96 articles by research streams. An analysis of

the different contextual settings where the social media

articles are found reveals that papers were related to sport

organizations (30.2%), sport consumers (29.1%), athletes

(19.8%), and journalism/media (18.8%).

As Table 1 indicates, publication of research on

social media in sport management started in 2008 and

began to increase in 2010, continuing ever since. The pro-

portion of research work with respect to the understanding

of the nature of social media increased during the rst

four years of the scholarship and then started steadily

declining over the past two years, which is believed to

be a natural development in the life cycle of new and

emerging scholarships (Hardin, 2014).

Social Media Scholarship in Sport Management Research 605

JSM Vol. 29, No. 6, 2015

Research Streams

The Nature of Social Media. Given the relative

newness of research on social media, the majority of the

literature sought to gain an understanding of (i) the use

of social media, (ii) users and their characteristics, and

(iii) adoption of the platforms. As can be seen in Table

1, 11 of the 15 published works during the early age of

the scholarship—2008 to 2010—were conducted to gain

an understanding of the nature of social media. This

continued until June 2014, as this research stream accounts

for over one-third (37.5%) of the literature published.

Figure 2 — Summary of the research streams. Note. SM = social media.

Table 1 Distribution of Research Papers by Research Stream

Research

Stream 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

a

Total

Nature of social

media

2 2 7 9 8 6 2 (36) 37.5%

Dening

constructs

— — 1 1 4 3 4 (13) 13.5%

Social media as

a tool

— 1 — 4 6 9 3 (23) 24%

Legal and ethical

considerations

— — — 4 — 3 1 (8) 8.3%

Industry

applications

1 — — — 1 2 3 (7) 7.3%

Issues and

impacts

— — 1 — — 8 — (9) 9.4%

Total (3) 3.1% (3) 3.1% (9) 9.4% (18) 18.8% (19) 19.8% (31) 32.3% (13) 13.5% (96) 100%

a

Publications in 2014 are only to June 2014 (i.e., 6 months).

606 Abeza et al.

JSM Vol. 29, No. 6, 2015

Understanding the Use of Social Media. A number

of articles explored and described social media as a

new communication medium by focusing on a specic

user group or context. For example, Hambrick and

Mahoney (2011) examined how professional athletes

used Twitter for promotional purposes. Similar studies

sought to understand how social media has been used

by fans (Sanderson, 2013), student-athletes (Browning

& Sanderson, 2012), professional athletes (Hambrick,

Frederick, & Sanderson, 2013; Hambrick, Simmons,

Greenhalgh, & Greenwell, 2010), and sport organizations

(Zimmerman, Clavio, & Lim, 2011), as well as in areas

such as marketing (Pegoraro & Jinnah, 2012), public

relations (Stoldt & Vermillion, 2013), and journalism

(Sheffer & Schultz, 2010).

Characteristics of Social Media Users. These papers

seek to gain an understanding of social media and

examine user characteristics. For example, one group of

scholars (Clavio, 2008; Clavio, Burch, & Frederick, 2012;

Clavio & Kian, 2010) investigated the characteristics of

users and usage proles of social media, examining user

characteristics, their demography, and their usage prole.

Adoption of Social Media Platforms. These researchers

investigate the preference for and acceptance of social

media platforms. O’Shea and Alonso (2011) examined

the ways in which three professional clubs are leveraging

traditional marketing approaches while adapting to social

media to an increasingly media-driven consumer base.

Similarly, Kassing and Sanderson (2010) examined how

fans experienced a major sporting event through the

content shared by cyclists using Twitter.

Defining Constructs. In this research stream, the

underlying constructs of users’ motivation, behavior,

attitude, and gratication in using social media were

investigated. In addition, useowners’ objectives in

adopting social media were examined. Most articles

in this stream addressed (i) the reasons why users are

using social media, and (ii) the constructs of acceptance

of social media. As can be seen in Table 1, this stream

of research is ranked third (13.5%) in terms of research

attention.

Dimensions of Use. Researchers attempted to identify

the reasons why (e.g., the motivations, behavior, and

attitude) audiences are using social media platforms.

For example, Frederick, Clavio, Burch, and Zimmerman

(2012) examined fans’ uses and gratification on a

mixed-martial-arts blog, and found six dimensions

of gratication: evaluation, community, information

gathering, knowledge demonstration, argumentation,

and diversion. Similarly, Clavio and Walsh (2013)

examined college sport fans’ dimensions of gratication

for social media use. In a related study, Stavros, Meng,

Westberg, and Farrelly (2014) explored the motivations

underpinning the desire of fans to communicate on the

Facebook sites of several NBA teams. Other researchers

have studied the dimensions of use in a different context.

For example, McCarthy (2014) studied the motivations,

behaviors, and media attitudes of fan sports bloggers.

Constructs of Acceptance and Platforms

Attributes.

Several researchers have attempted

to investigate the constructs for the acceptance of

social media. For example, Mahan (2011) examined

predictors of consumer preferences for social media

and Pronschinske, Groza, and Walker (2012) examined

the Facebook attributes that attract the most fans based

on four professional teams. Witkemper, Lim, and

Waldburger (2012) examined the motives and constraints

that influence individuals’ adoption of Twitter as a

medium to follow their favorite athletes.

Social Media as a Tool. Under this research stream,

the use and services of social media as communication

platforms and marketing tools were examined. This

stream accounts for the second largest portion (24%) of

the social media scholarship (see Table 1).

Social Media as a Communication Tool. Various

sociocultural discussions are communicated through

social media, and these have been examined by a

number of studies. Topics explored include fandom and

advocacy for women’s sports in blog posts (Antunovic &

Hardin, 2012), crisis communication on Twitter (Brown

& Billings, 2013; Brown, Brown, & Billings, 2013),

portrayal of women in sports blogs (Clavio & Eagleman,

2011), fans’ views on racism on message boards (Cleland,

2013), professional athletes’ self-presentation on Twitter

(Lebel & Danylchuk, 2012), framing self on Twitter

(Coche, 2014), and fans’ creation and maintenance of

social capital on Facebook (Phua, 2012).

Social Media as a Marketing Tool. Other studies

examined sport organizations’ use of social media as

a marketing communication tool. Examples include

Eagleman’s (2013) investigation of national sport

organizations’ use of social media as a marketing

communication tool, and Dittmore, McCarthy, McEvoy,

and Clavio’s (2013) examination of intercollegiate

athletic administrators’ perceived utility of Twitter as a

form of marketing or communication. Other examples

include Hambrick and Kang’s (2014) exploration of

professional sports organizations’ use of Pinterest as a

communications and relationship-marketing tool, and

Wallace, Wilson, and Miloch’s (2011) examination

of college sport organizations’ use of Facebook for

marketing and communications.

Legal and Ethical Considerations. Under the fourth-

largest research stream, various legal and ethical issues

associated with social media use and its implications

were investigated. Although only a few articles addressed

legal and ethical issues, two distinct categories can be

identied: (i) legal considerations in using social media,

and (ii) student-athletes and social media use policies.

This research stream covers 8.3% of the published work.

Social Media Scholarship in Sport Management Research 607

JSM Vol. 29, No. 6, 2015

Legal Considerations in Using Social Media. Studies

that discussed the legal issues related to social media

covered topics such as potential legal issues related to

social media use (Cornish & Larkin, 2014; Wendt &

Young, 2011), and athletes’ product endorsement on

social media (Brison, Baker, & Byon, 2013; McKelvey

& Masteralexis, 2013).

Student-Athletes and Social Media Use Policies.

Under this category, researchers (Sanderson, 2011; Sand-

erson & Browning, 2013) examined the messages that

student-athletes receive from athletic department ofcials

and coaches about social media use. Van Namen (2011)

explored the need for coaches, athletic departments, and

university administrators to monitor and regulate student-

athletes’ use of social media without facing potential legal

exposure for infringement of constitutionally protected

free speech rights. The studies provided insight into social

media use policy in college sport.

Industry Applications. Although many sport

organizations have embraced social media platforms

with the aim of delivering their products and services

competitively, a small proportion of the published

research (7.3%), as noted in Table 1, is about the industry

application of social media. These seven studies are

grouped into one subcategory: social media marketing

strategy.

Social Media Marketing Strategy. The strategic

use of social media and its integration into an overall

communication strategy have been addressed by authors

such as Armstrong, Delia, and Giardina (2014), who

analyzed the social media marketing strategies of the

Los Angeles Kings; Boehmer and Lacy (2014), who

investigated the implementation of an interactive social-

customer relationship-management strategy on Facebook;

and Bayne and Cianfrone (2013), who examined social

media marketing effectiveness on college students in a

campus recreation setting. Further, Miranda, Chamorro,

Rubio, and Rodriguez (2014) employed the Facebook

Assessment Index to compare, assess, and rank Facebook

sites of top European and North American professional

teams.

Issues and Impacts. Articles under this research

stream considered the impacts and issues related to social

media use and their implications, such as impact on sport

brand and journalism practice, and the opportunities,

constraints, and challenges of social media as a

communication and marketing tool. This research stream

accounts for 9.4% of the scholarship and the studies are

classied as (i) impact of social media use on journalism

practice and (ii) issues and impacts of social media in

marketing practices.

Impact of Social Media on Journalism Practice. In

the topic area of journalism practice, Gibbs and Haynes

(2013) attempted to explain how the practices and norms

related to the role of sport media relations are changing as

a result of Twitter. McEnnis (2013) examined what citizen

journalism on Twitter has meant for the professional

identity and working practices of British sport journalists,

and Reed and Hansen (2013) examined how American

sport journalists’ (particularly those who cover elite

sports) perception of gatekeeping has changed since they

began using social media for news-gathering purposes.

Schultz and Sheffer (2010) assessed what changes Twitter

has caused in journalism news work.

Issues and Impacts of Social Media in Marketing

Practices.

A small number of researchers addressed

the impact and issues of social media on the practice

of marketing. For example, Walsh, Clavio, Lovell, and

Blaszka (2013) studied the impact of social media use on

sport brands, and O’Shea and Alonso (2013) examined

how an Australian professional sports organization

addressed the potentials and constraints of social media

usage, while Abeza et al. (2013) explored the use,

opportunities, and challenges of social media in meeting

relationship marketing goals.

Contribution of Research Papers

by Academic Journals

Of the 29 journals that featured the 96 articles, only 2

journals (International Journal of Sport Communication

[IJSC] and Sociology of Sport Journal) published social

media research papers in sport management in the period

2008–2010. In 2011, 9 other journals joined them, and,

since, both the number of journals publishing social

media articles and the number of published social media

research papers have increased. A signicant increase in

the number of journals from 2010 (10 journals) to 2013

(18 journals) was observed. Table 2 reveals that 80.2%

of the articles are published by 10 of the 29 journals,

led by IJSC (40.6%). Further, Communication & Sport

published 8 social media articles in just over a year of its

existence. The other three journals that published social

media articles relatively frequently include International

Journal of Sport Management and Marketing (7), Journal

of Sports Media (6), and Sport Marketing Quarterly (5).

As reported in Table 2, social media publication in

sport management research has a short history that is

characterized by a rapidly increasing body of literature.

Platforms That Received the (Most/Least)

Attention in the Research Community

The social media platform that received the most atten-

tion is Twitter (41.7%), followed by Facebook (12.5%),

and Blogs (10.4%). These three platforms take the main

share (64.6%) of the social media sport management

research. Studies that covered a combination of Facebook

and Twitter, a combination of other platforms, or social

media in general account for 28.12% of the published

works. Other platforms that received scholars’ attention

include message boards (3 articles), YouTube (2 articles),

608 Abeza et al.

JSM Vol. 29, No. 6, 2015

Table 2 Distribution of Research Papers by Journal and Period

No. Journal 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

a

Total

1 Intl. Journal of Sport Communication 3 1 9 4 10 7 5 39

2 Communication & Sport 4 4 8

3 Intl. Journal of Sport Management and Marketing 5 2 7

4 Journal of Sports Media 1 2 2 1 6

5 Sport Marketing Quarterly 2 2 1 5

6 Sociology of Sport Journal 2 1 3

7 Sport Management Review 2 1 3

8 Journal of Sport Administration & Supervision 1 1 2

9 Mississippi Sports Law Review 2 2

10 Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics 1 1 2

11 Journal of Legal Aspects of Sport 1 1

12 Journal of Sport Management 1 1

13 Computers in Human Behavior 1 1

14 Information, Communication & Society 1 1

15 Intl. Journal of Integrated Marketing Communications 1 1

16 Intl. Journal of Motorsport Management 1 1

17 Intl. Journal of Networking and Virtual Organizations 1 1

18 Intl. Journal of Sports Science and Coaching 1 1

19 Intl. Journal of Web Based Communities 1 1

20 Journal of Brand Strategy 1 1

21 Journal of Sport & Social Issues 1 1

22 Journalism Practice 1 1

23 Leisure Studies 1 1

24 Mass Communication and Society 1 1

25 Public Relations Review 1 1

26 Qualitative Research Reports in Communication 1 1

27 Recreational Sports Journal 1 1

28 Soccer & Society 1 1

29 Virginia Sports and Entertainment Law Journal 1 1

Total 3 3 9 18 19 31 13 96

a

Publications in 2014 are only to June 2014 (i.e., 6 months).

Pinterest (1 article), and Weibo (1 article). When an article

looked at two or more platforms together, such as Twit-

ter, Facebook, and LinkedIn (see Cornish and Larkin,

2014), the article is classied under the umbrella name

social media.

Theories in Social Media Scholarship

in Sport Management Research

The article review identied 26 theories and theoretical

models used or referenced in 52 of the 96 articles origi-

nating from a variety of disciplines such as sociology,

marketing, psychology, information technology, mass

media, and crisis communication (see Appendix Table

2). Uses and gratications, and relationship marketing

theories are the most cited theories (being used in 10

and 7 studies, respectively). Parasocial interaction and

agenda setting have been used in four studies, while

media framing, social identity theories, and image/reputa-

tion repair typology were each used in three studies. The

theory of self-presentation, the technology acceptance

model, and gatekeeping theory have each been used in

two social media studies each. The remaining 15 theories

and models have each been used once.

Social Media Scholarship in Sport Management Research 609

JSM Vol. 29, No. 6, 2015

The 52 studies that made reference to the 26 identi-

ed theories were classied into Bryant and Miron’s

(2004) 11 groupings of theory utilization: (i) mere refer-

ences, (ii) using as theoretical framework, (iii) compari-

son of two or more theories, (iv) critique of a theory or of

theories, (v) proposing a theory, (vi) supporting a theory,

(vii) testing a new theory, (viii) integrating theories, (ix)

expanding a theory, (x) new application, and (xi) praising

of a theory or of theories. The classication is presented

as Table 3, which reports that 69.8% used their theories

as a framework for the study and 9.4% of the articles

expanded the theories or models referenced. Other uses

of theory reported are mere references to the theories

(7.5%), supporting theories (3.8%), and new application

of theories into social media studies (3.8%). Integration of

theories also accounted for 3.8% (e.g., Frederick, Lim, et

al. [2012] integrated/combined uses and gratication and

parasocial interaction in their study), and discussion of a

theory/praising (e.g., Williams and Chinn [2010]: rela-

tionship marketing) accounted for 1.9%. Those aspects

typically considered to be the primary components of

theory construction (Bryant & Miron, 2004), such as

proposing a theory, testing a new theory, critique of a

theory, and comparison of theories are absent in social

media scholarship in sport management research.

Research Methods in Social Media

Scholarship in Sport Management

Research

Research and Data-Gathering Methods. The

proportion of the research methodologies/methods used

in social media articles in sport management research

is presented in Table 4. The table reports that the

quantitative method (51.1%) is the most used method

in social media scholarship, followed by qualitative

methods (43.2%). Over the 6.5-year period analyzed, the

use of qualitative methods is increasing. The use of both

mixed- and multimethod research approaches is limited.

Table 5 reports on the data collection methods in

social media sport management research, where content

analyses (50.5%) and surveys (29.7%) far exceeded any

other method of data gathering during the 6.5-year period

analyzed. Interviews ranked third (16.5%) followed by

experimental methods (2.2%). Field notes were used in

only one study.

Discussion and Directions

for Future Research

Social media has attracted signicant sport management

research interest since 2008, a trend consistent with the

popularity of social media platforms in the sport industry.

While the reviewed articles provided insights into the

features, use, benets, opportunities, impacts, and chal-

lenges of social media, this study nds that there are broad

areas in need of attention. The results can be summarized

as follows: (a) the social media literature provides a solid

foundation for an understanding of social media in sport

management research, (b) a signicant concentration of

the sport management research is on the topic of two

social media platforms—Twitter and Facebook, (c) the

Table 3 References to Theories

Utilization of Theories No. of Studies

Theoretical framework for the study (36) 69.8%

Expanding a theory (5) 9.4%

Mere references (4) 7.5%

Supporting a theory (2) 3.8%

New application (2) 3.8%

Integrating/combining theories (2) 3.8%

Praising/detail discussion (1) 1.9%

Proposing a theory —

Testing a new theory —

Comparison of two or more theories —

Critique of a theory or of theories —

(52) 100%

Table 4 Research Methods in Social Media Scholarship

Methodology 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

a

Total

Quantitative 2 — 4 9 11 12 7 (45) 51.1%

Qualitative 1 2 3 5 9 15 3 (38) 43.2%

Multimethod — — 1 — — 2 — (3) 3.4%

Mixed Method — — — — 1 1 (2) 2.3%

Total 3 2 8 14 20 30 11 88

b

a

Publications in 2014 are only to June 2014 (i.e., 6 months).

b

The total number is less than the 96 articles reviewed because some articles in elds like law and sociology

publish more of analytical/descriptive papers and did not employ a specic traditional research method.

610 Abeza et al.

JSM Vol. 29, No. 6, 2015

utilization of theories is still in the early stages, (d) there

is a limited scope and range in the research methods

adopted and data collection instruments employed, and

(e) there is a lack of a framework that provides a sum-

mary of the current literature and provides direction for

future research.

In summary, the relative newness of the social media

scholarship in sport management is observed in the trends

of emerging research streams, in the application of refer-

enced theories, and in the scope of the research methods

employed. This “state” is in line with the logical steps in

the life cycle of an emerging area of scholarship (Hardin,

2014). Importantly, this stage of the scholarship and its

associated developmental reality should not be seen as

disadvantages. In fact, to the contrary, once the research

community becomes aware of the state of the scholar-

ship and is provided with a framework, it will be in a

position to take the next step(s) toward developing more

sophisticated research questions, covering broader topics,

advancing the utilization of theories, and expanding the

research methods employed. Specically, the literature

produced to date provides the starting point toward the

continued development of the eld (see Hardin, 2014),

and provides the future research directions. Further, the

reported lack of social media research among scholars

in key areas of sport management—such as nance,

governance, organizational behavior, development, tour-

ism, facility management, and event management—is a

deterrent to the growth of research in the area. This must

be addressed in sport management doctoral programs in

these areas, with students being provided with the tools

necessary to conduct social media research in nance,

event management and the other identied areas.

Results support that the overall impact and sig-

nicance of social media in the contemporary sport

industry has remained unexplored in a number of the

subdisciplines of sport management. In particular, the

focus has been on sport marketing and sport commu-

nications. Intuitively, this is expected given the roots of

social media as a communication form that marketers

can easily incorporate into their activities. Thus, for the

eld to move forward, the onus falls to the marketing and

communications scholars to build theory, expand empiri-

cal analyses, and provide strong frameworks for the sport

management scholars in the other subdisciplines. Since

social media is, by nature, a communication platform,

the focus on sport marketing and communication to date

makes sense. However, the study of the dynamic inter-

relationship between sport and social media has a cross-

disciplinary nature (Pedersen, 2013) and with the body

of literature to date, attention to the other subdisciplines

of sport management is needed. As can be seen from the

emergent research streams, the studies produced to date in

three of the subelds of sport management have already

laid substantial foundation for future advancements.

These include sport marketing, sport communication

and sport law. In sport law, for instance, various legal

issues that arise from uses and misuses of social media

have been explored in the work of Brison et al. (2013),

McKelvey and Masteralexis, (2013), Cornish and Larkin

(2014), Van Namen (2011), Wendt and Young (2011), and

Sanderson (2011).

In the topic area of crisis communication, the works

of Sanderson (2013), Hambrick et al. (2013), Brown

et al. (2013), and Brown and Billings (2013) serve as

groundwork for future studies. In the three subdisciplines

themselves, however, a number of research opportunities

await research attention. In sport marketing, for example,

there exists limited research on the impact, role, and

signicance of social media as a platform for advertis-

ing, sales, direct marketing, sponsorship, branding, and

ambush marketing. In sponsorship, for instance, social

media has a natural appeal as an activation tool for both

the sponsor and the sponsee. Resulting from its instant

global reach, ease of networking, and ease of collabora-

tion, social media has become a powerful marketing tool

Table 5 Proportions of Data-Gathering Methods

Data Gathering Method 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

a

Total

Content Analysis

b

1 2 5 7 9 14 8

c

(46) 50.5%

Survey/Questionnaire 2 — 2 4 9 7 3

c

(27) 29.7%

Interview — — — 3 3 8 1

c

(15) 16.5%

Experimental — — 1 — — 1 — (2) 2.2%

Observation/Field Notes — — — — — — 1 (1) 1.1%

Total 3 2 8 14 21

b

30 13

c

91

c

a

Publications in 2014 are only until June 2014 (i.e., 6 months).

b

Content analysis: quantitative content analysis = 18; qualitative content analysis = 25 (content analysis = 13, thematic analysis = 5, textual analysis

= 3, discourse analysis = 2, social network analysis = 2). Note. Whereas content analysis is an analytical approach in research methods, here it is

used to refer to a secondary source data that was gathered from social media sites and analyzed to produce themes or quantitative data. Content is

also considered to include text, photo, and video. Therefore, for the purpose of this work, analytical approaches such as textual analysis, thematic

analysis, and discourse analysis are grouped under content analysis.

c

It should have been reported as 88. However, as the summary in Table 4 indicates, one mixed method study (i.e., Gibbs, O’Reilly, & Brunette, 2014)

used three methods (interviews, content analysis, and survey).

Social Media Scholarship in Sport Management Research 611

JSM Vol. 29, No. 6, 2015

(Kotler, 2011), particularly for those seeking to market in

multiple countries. Therefore, investigating how sponsors

and sponsees are reacting to the ever-changing nature

of sporting landscapes resulting from social media will

inform both scholars and practitioners.

In the very early days of the social media scholarship,

Leonard (2009) argued that there was a need:

. . . to react to the ever changing nature of sporting

landscapes resulting from innovation and technologi-

cal changes, not simply categorizing metamorpho-

sis as indicative of the new media era of sport but

reecting on the impact and signicance of these

transformations. (p. 12)

This recommendation is still very relevant today, and

research needs to keep pace with these changes. Indeed,

as opposed to the current approach that considers all audi-

ences/users of social media as identical, future research

should progress to identify, differentiate, and take into

account differences in the behavior of social media users

and their level of involvement. Today’s social media users

dedicate substantial time to producing and consuming

multimedia content, and are found to be the foremost

players in all categories of Web 2.0 applications. This is

why the terms prosumer and user-generated content are

often used to underline the fact that today’s users are not

only consumers, but also the prime content contributors.

These users exhibit different levels of commitment and

participation on social media platforms, ranging from

passive visitor to committed contributor.

Various researchers (e.g., Harridge-March &

Quinton, 2009; Kozinets, 2006; Riegner, 2007) have

attempted to develop different classications of social

media users. For example, Harridge-March and Quinton

(2009) proposed that social media users could be clas-

sied by their level of involvement, namely as lurkers,

newbies/tourists, minglers, and evangelists/devotees. In

a similar manner, audiences (i.e., friends on Facebook

or followers on Twitter) of a social media site are not

all necessarily supporters of the useowners/social media

site owners, and not all ofine fans of a useowner are

necessarily users of social media (Abeza et al., 2013).

For these reasons, future studies need to factor in the

differences in behavior exhibited by social media users

and differences by that users’ level of involvement should

be accounted for. In particular, inuential users should

be given specic research attention. Related exemplary

studies in this area include Clavio and Walsh (2013) and

Stavros et al. (2014).

With respect to the results reported on platforms,

while it can be justied why the majority of research

focused on Twitter and Facebook, research on the other

platforms will serve to inform both scholars and practi-

tioners. In this regard, the studies on YouTube (Mahoney,

Hambrick, Svensson, & Zimmerman, 2013; Zimmer-

man et al. 2011), Pinterest (Hambrick & Kang, 2014)

and Weibo (Liu & Berkowitz, 2013) are exemplary. A

number of researchers (Frederick, Lim, Clavio, Pedersen,

& Burch, 2014; Pronschinske et al., 2012; Walsh et al.,

2013; Witkemper et al., 2012) recommend research be

conducted across multiple platforms.

Concerning theories, the majority of research (75%)

use theories specically as a tool to frame their studies.

Although theory development helps a scholarship build

its identity and increase its self-reliance (Abeza et al.,

2014), there is a dearth in studies that propose a theory,

test a new theory, critique a theory, or compare different

theories. This requires research attention as very few

studies were found that support existing theories, apply

theories from other areas of study in social media setting,

and integrate different theories. Although proposing,

testing, critiquing and comparing theories is not common

in an emerging area of scholarship, results suggest that

this is now a challenge for the social media research

community, as the scholarship continues to advance.

Hence, sport management researchers in social media are

encouraged to compare, critique, integrate theories, test

and apply theories from other elds into the context of

social media, and begin developing new theories. More-

over, as Slack (1998) stated, scholars not only need to

use existing theories to study sport but also to use sport

to test and extend existing theories.

And nally, with regards to research methods, a

small range of data collection methods are being used in

social media scholarship in sport management research:

content analysis, online surveys, and interviews. Results

on research methods employed in social media sport

management studies differ from what are known to be

the most common sources of data collection in qualitative

research (i.e., document and archival analysis, direct and

participant observation, focus groups, interviews) (Yin,

2014) and in quantitative research (i.e., experiments,

questionnaires) (Creswell, 2014). Thus, a more diverse

set of methods is encouraged.

While a thematic analysis of various sports stake-

holders’ social media use has value, and while such

studies have importance and, therefore, should be pursued

(Sanderson, 2014), the size of samples and number of

cases are areas that should be improved. For instance,

some of the interviews were based on single cases, when

multiple cases could have been employed. In fact, con-

trary to much of the existing literature, a single case or

unit of analysis should only be justiable when the case

(e.g., an athlete, an organization, a coach, an incident)

is either a representative, critical, extreme or unique, or

when it is typical or revelatory (Yin, 2014). This recom-

mendation is supported by previous authors (e.g., Alonso

& O’Shea, 2012b, Hambrick & Sanderson, 2013) who

contend that researchers would be well served to consider

multiple cases in their sampling.

In addition, as Pedersen (2014) stated, scholars should

address some of the research questions using relatively

challenging methods such as ethnography and experi-

mental study (when appropriate). It is also pertinent (and

recommended) for scholars to consider longitudinal stud-

ies. In this regard, after noting the shifting nature of social

media, a number of authors (see Hambrick & Mahoney,

612 Abeza et al.

JSM Vol. 29, No. 6, 2015

2011; Mahan, Seo, Jordan, & Funk, 2014; Pronschinske

et al. 2012; Sanderson & Hambrick, 2012; Stoldt & Ver-

million, 2013) have suggested that a longitudinal study be

conducted over time to gain a deeper understanding as to

whether various stakeholders in the sport industry (e.g.,

celebrity athletes, sport organizations, sport consumers,

journalists) can develop increasingly sophisticated ways to

use social media. Further, it is worth noting that advances

in data mining and analytics software programs have

made possible the ability to sort, retrieve, collect, compile

and analyze a vast volume of data in a shorter period of

time. There are number of software programs that can be

used for data gathering (e.g., NCapture, DiscoverText,

SiteSucker, Netlytic) and as content analysis tools (e.g.,

Leximancer, NVivo). These software programs enable

scholars to address the problem of analyzing a small

number of content, and to enhance intercoder reliability

(Sotiriadou, Brouwers, & Le, 2014). Critical reviews

similar to the one at hand are encouraged on a periodical

basis, and it is hoped that future work will address and

take into consideration those recommendations.

Finally, although this research set out to provide a

thorough, critical review of the available literature on

social media in sport management research, the study

has limitations. First, the topics addressed in the research

are limited to those discussed in the literature and do not

necessarily include all facets of social media that warrant

scholarly inquiry. For example, as noted, sponsorship acti-

vation is an area where research on social media would be

of high value. Second, only literature accessible through

electronic databases is considered, where some articles

may have been missed in the keyword search.

References

Abeza, G., O’Reilly, N., & Nadeau, J. (2014). Sport commu-

nication: A multi-dimensional assessment of the eld’s

development. International Journal of Sport Communica-

tion, 7(3), 289–316. doi:10.1123/IJSC.2014-0034

Abeza, G., O’Reilly, N., & Reid, I. (2013). Relationship mar-

keting and social media in sport. International Journal of

Sport Communication, 6(2), 120–142.

Alonso, A.D., & O’Shea, M. (2012a). “You are invisible”: Mar-

keting professional sports in the technology era. Journal

of Sports Media, 7(2), 1–21. doi:10.1353/jsm.2012.0016

Alonso, A.D., & O’Shea, M. (2012b). Moderating virtual

sport consumer forums: Exploring the role of the vol-

unteer moderator. International Journal of Networking

and Virtual Organisations, 11(2), 173–187. doi:10.1504/

IJNVO.2012.048332

Andrew, D.P., Pedersen, P.M., & McEvoy, C.D. (2011).

Research methods and design in sport management.

Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Antunovic, D., & Hardin, M. (2012). Activism in women’s

sports blogs: Fandom and feminist potential. International

Journal of Sport Communication, 5(3), 305–322.

Armstrong, C.G., Delia, E.B., & Giardina, M.D. (2014).

Embracing the social in social media an analysis of the

social media marketing strategies of the Los Angeles

Kings. Communication & Sport. Advance online publica-

tion. doi:10.1177/2167479514532914

Askool, S., & Nakata, K. (2011). A conceptual model for

acceptance of social CRM systems based on a scoping

study. AI & Society, 26(3), 205–220. doi:10.1007/s00146-

010-0311-5

Bayne, K.S., & Cianfrone, B.A. (2013). The effectiveness of

social media marketing: The impact of Facebook status

updates on a campus recreation event. Recreational Sports

Journal, 37(2), 147–159.

Billings, A.C., & Hardin, M. (Eds.). (2014). Routledge hand-

book of sport and new media. New York, NY: Routledge.

Blaszka, M., Burch, L.M., Frederick, E.L., Clavio, G., & Walsh,

P. (2012). #WorldSeries: An empirical examination of a

Twitter hashtag during a major sporting event. Interna-

tional Journal of Sport Communication, 5(4), 435–453.

http://journals.humankinetics.com/ijsc-back-issues/ijsc-

volume-5-issue-4-december

Boehmer, J., & Lacy, S. (2014). Sport news on Facebook: The

Relationship between interactivity and readers’ browsing

behavior. International Journal of Sport Communication,

7(1), 1–15. doi:10.1123/IJSC.2013-0112

Brison, N., Baker, T., & Byon, K. (2013). Tweets and crumpets:

Examining U.K. and U.S. regulation of athlete endorse-

ments and social media marketing. Journal of Legal

Aspects of Sport, 23, 55–71.

Brown, N.A., & Billings, A.C. (2013). Sports fans as crisis

communicators on social media websites. Public Relations

Review, 39(1), 74–81. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.09.012

Brown, N.A., Brown, K.A., & Billings, A.C. (2013). “May

No Act of Ours Bring Shame”: Fan-enacted crisis com-

munication surrounding the Penn State sex abuse scandal.

Communication & Sport. Advance online publication.

doi:10.1177/2167479513514387

Browning, B., & Sanderson, J. (2012). The positives and nega-

tives of Twitter: Exploring how student-athletes use Twitter

and respond to critical tweets. International Journal of

Sport Communication, 5(4), 503–521.

Bryant, J., & Miron, D. (2004). Theory and research in mass

communication. Journal of Communication, 54(4),

662–704. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2004.tb02650.x

Burch, L.M., Frederick, E.L., Zimmerman, M.H., & Clavio,

G.E. (2011). Agenda-setting and La Copa Mundial:

Marketing through agenda-setting on soccer blogs during

the 2010 World Cup. International Journal of Sport Man-

agement and Marketing, 10(3/4), 213–231. doi:10.1504/

IJsocial mediaM.2011.044791

Chalip, L. (2006). Toward a distinctive sport management

discipline. Journal of Sport Management, 20(1), 1–21.

Clavio, G. (2008). Demographics and usage proles of users

of college sport message boards. International Journal of

Sport Communication, 1(4), 434–443.

Clavio, G. (2011). Social media and the college football audience.

Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics, 4, 309–325.

Social Media Scholarship in Sport Management Research 613

JSM Vol. 29, No. 6, 2015

Clavio, G., Burch, L.M., & Frederick, E.L. (2012). Networked

fandom: Applying systems theory to sport Twitter analy-

sis. International Journal of Sport Communication, 5(4),

522–538.

Clavio, G., Walsh, P., & Vooris, R. (2013). The utilization of

Twitter by drivers in a major racing series. International

Journal of Motorsport Management, 2(1), Article 2.

Clavio, G., & Eagleman, A.N. (2011). Gender and sexually

suggestive images in sports blogs. Journal of Sport Man-

agement, 7, 295–304.

Clavio, G., & Kian, T.M. (2010). Uses and gratications of a

retired female athlete’s Twitter followers. International

Journal of Sport Communication, 3(4), 485–500.

Clavio, G., & Walsh, P. (2013). Dimensions of social

media utilization among college sport fans. Com-

munication & Sport. Advance online publication.

doi:10.1177/2167479513480355.

Cleland, J. (2013). Racism, football fans, and online mes-

sage boards: How social media has added a new

dimension to racist discourse in English football.

Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 38, 415–431.

doi:10.1177/0193723513499922

Coche, R. (2014). How golfers and tennis players frame

themselves: A content analysis of Twitter prole pictures.

Journal of Sports Media, 9(1), 95–121. doi:10.1353/

jsm.2014.0003

Constantinides, E., & Fountain, S. (2008). Web 2.0: Concep-

tual foundations and marketing issues. Journal of Direct

Data and Digital Marketing Practice, 9(3), 231–244.

doi:10.1057/palgrave.dddmp.4350098

Cornish, A.N., II, & Larkin, B. (2014). Social media’s changing

legal landscape provides cautionary tales of “Pinterest” to

sport marketers. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 23(1), 47–49.

Cornwell, T.B., & Maignan, I. (1998). An international review

of sponsorship research. Journal of Advertising, 27(1),

1–21. doi:10.1080/00913367.1998.10673539

Costa, C. (2005). The status and future of sport management:

A Delphi study. Journal of Sport Management, 19(2),

117–142.

Creswell, J.W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quanti-

tative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks,

CA: Sage.

Cunningham, N., & Bright, L.F. (2012). The tweet is in your

court: Measuring attitude towards athlete endorsements in

social media. International Journal of Integrated Market-

ing Communications, 4(2), 73–87.

Dart, J.J. (2009). Blogging the 2006 FIFA World Cup Finals.

Sociology of Sport Journal, 26(1), 107–126.

Deprez, A., Mechant, P., & Hoebeke, T. (2013). Social media

and Flemish sports reporters: A multimethod analysis of

Twitter use as journalistic tool. International Journal of

Sport Communication, 6(2), 107–119.

Dittmore, S.W., McCarthy, S.T., McEvoy, C., & Clavio, G.

(2013). Perceived utility of ofcial university athletic

Twitter accounts: The opinions of college athletic admin-

istrators. Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics, 6,

286–305.

Dittmore, S.W., Stoldt, G.C., & Greenwell, T.C. (2008). Use of

an organizational weblog in relationship building: The case

of a Major League Baseball team. International Journal

of Sport Communication, 1(3), 384–397.

Doherty, A. (2013). “It takes a village:” Interdisciplinary

research for sport management. Journal of Sport Manage-

ment, 27(1), 1–10.

Drury, G. (2008). Opinion piece: Social media—Should mar-

keters engage and how can it be done effectively? Journal

of Direct, Data and Digital Marketing Practice, 9(3),

274–277. doi:10.1057/palgrave.dddmp.4350096

Eagleman, A.N. (2013). Acceptance, motivations, and usage

of social media as a marketing communications tool

amongst employees of sport national governing bodies.

Sport Management Review, 16(4), 488–497. doi:10.1016/j.

smr.2013.03.004

Emmons, B., & Butler, S. (2013). Institutional constraints and

changing routines: Sports journalists tweet the Daytona

500. Journal of Sports Media, 8(1), 163–187. doi:10.1353/

jsm.2013.0004

Frederick, E.L., Burch, L.M., & Blaszka, M. (2013). A

shift in set: Examining the presence of agenda set-

ting on Twitter during the 2012 London Olympics.

Communication & Sport. Advance online publication.

doi:10.1177/2167479513508393

Frederick, E.L., Clavio, G.E., Burch, L.M., & Zimmerman,

M.H. (2012). Characteristics of users of a mixed-martial-

arts blog: A case study of demographics and usage trends.

International Journal of Sport Communication, 5(1),

109–125.

Frederick, E.L., Lim, C.H., Clavio, G., & Walsh, P. (2012).

Why we follow: An examination of parasocial interaction

and fan motivations for following athlete archetypes on

Twitter. International Journal of Sport Communication,

5(4), 481–502.

Frederick, E., Lim, C.H., Clavio, G., Pedersen, P.M., & Burch,

L.M. (2014). Choosing between the one-way or two-way

street: An exploration of relationship promotion by profes-

sional athletes on Twitter. Communication & Sport, 2(1),

80–99. doi:10.1177/2167479512466387

Gibbs, C., & Haynes, R. (2013). A phenomenological investiga-

tion into how Twitter has changed the nature of sport media

relations. International Journal of Sport Communication,

6(4), 394–408.

Gibbs, C., O’Reilly, N., & Brunette, M. (2014). Professional

team sport and Twitter: Gratications sought and obtained

by followers. International Journal of Sport Communica-

tion, 7(2), 188–213. doi:10.1123/IJSC.2014-0005

Hambrick, M.E. (2012). Six degrees of information: Using

social network analysis to explore the spread of informa-

tion within sport social networks. International Journal

of Sport Communication, 5(1), 16–34.

Hambrick, M.E., & Kang, S.J. (2014). Pin it: Exploring

how professional sports organizations use Pinterest

as a communications and relationship-marketing tool.

Communication & Sport. Advance online publication.

doi:10.1177/2167479513518044

614 Abeza et al.

JSM Vol. 29, No. 6, 2015

Hambrick, M.E., & Mahoney, T.Q. (2011). ‘It’s incredible—

trust me’: Exploring the role of celebrity athletes as mar-

keters in online social networks. International Journal

of Sport Management and Marketing, 10(3/4), 161–179.

doi:10.1504/IJsocial mediaM.2011.044794

Hambrick, M.E., & Sanderson, J. (2013). Gaining primacy in the

digital network: Using social network analysis to examine

sports journalists’ coverage of the Penn State football

scandal via Twitter. Journal of Sports Media, 8(1), 1–18.

doi:10.1353/jsm.2013.0003

Hambrick, M.E., Frederick, E.L., & Sanderson, J. (2013).

From yellow to blue: Exploring Lance Armstrong’s image

repair strategies across traditional and social media.

Communication & Sport. Advance online publication.

doi:10.1177/2167479513506982

Hambrick, M.E., Simmons, J.M., Greenhalgh, G.P., & Green-

well, T.C. (2010). Understanding professional athletes’

use of Twitter: A content analysis of athlete tweets. Inter-

national Journal of Sport Communication, 3(4), 454–471.

Hardin, M. (2014). Moving beyond description putting Twitter

in (theoretical) context. Communication & Sport, 2(2),

113–116. doi:10.1177/2167479514527425

Harridge-March, S., & Quinton, S. (2009). Virtual snakes and

ladders: Social networks and the relationship market-

ing loyalty ladder. Marketing Review, 9(2), 171–181.

doi:10.1362/146934709X442692

Havard, C.T., Eddy, T., Reams, L., Stewart, R.L., & Ahmad,

T. (2012). Perceptions and general knowledge of online

social networking activity of university student-athletes

and non-student-athletes. Journal of Sport Administration

& Supervision, 4(1), 14–31.

Hopkins, J.L. (2013). Engaging Australian Rules Football fans

with social media: A case study. International Journal

of Sport Management and Marketing, 13(1/2), 104–121.

doi:10.1504/IJsocial mediaM.2013.055197

Hull, K. (2014). A hole in one (hundred forty characters): A case

study examining PGA Tour golfers’ twitter use during the

Masters. International Journal of Sport Communication,

7(2), 245–260. doi:10.1123/IJSC.2013-0130

Hull, K., & Lewis, N.P. (2014). Why Twitter displaces broadcast

sports media: A model. International Journal of Sport

Communication, 7(1), 16–33. doi:10.1123/IJSC.2013-

0093

Hutchins, B. (2011). The acceleration of media sport culture:

Twitter, telepresence and online messaging. Information

Communication and Society, 14(2), 237–257. doi:10.108

0/1369118X.2010.508534

Hutchins, B. (2014). Twitter follow the money and look

beyond sports. Communication & Sport, 2(2), 122–126.

doi:10.1177/2167479514527430

Kaplan, A.M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite!

The challenges and opportunities of social media. Business

Horizons, 53(1), 59–68. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003

Kaplan, A.M., & Haenlein, M. (2012). Social media: Back

to the roots and back to the future. Journal of Sys-

tems and Information Technology, 14(2), 101–104.

doi:10.1108/13287261211232126

Kassing, J.W., & Sanderson, J. (2010). Fan-athlete interaction

and Twitter tweeting through the Giro: A case study. Inter-

national Journal of Sport Communication, 3(1), 113–128.

Kian, E.M., Burden, J.W., Jr., & Shaw, S.D. (2011). Internet

sport bloggers: Who are these people and where do they

come from? Journal of Sport Administration & Supervi-

sion, 3(1), 30–43.

Kotler, P. (2011). Reinventing marketing to manage the environ-

mental imperative. Journal of Marketing, 75(4), 132–135.

doi:10.1509/jmkg.75.4.132

Kozinets, R.V. (2006). Click to connect: Netnography and

tribal advertising. Journal of Advertising Research, 46(3),

279–288. doi:10.2501/S0021849906060338

Kwak, D.H., Kim, Y.K., & Zimmerman, M.H. (2010). User-

versus mainstream-media-generated content: Media

source, message valence, and team identication and

sport consumers’ response. International Journal of Sport

Communication, 3(4), 402–421.

Lebel, K., & Danylchuk, K. (2012). How Tweet it is: A gendered

analysis of professional tennis players’ self-presentation

on Twitter. International Journal of Sport Communication,

5(4), 461–480.

Leonard, D.J. (2009). New media and global sporting cultures:

Moving beyond the clichés and binaries. Sociology of Sport

Journal, 26(1), 1–16.

Lievrouw, L. (2014). Alternative and activist new media.

Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Liu, Z., & Berkowitz, D. (2013). “Love sport, even when it

breaks your heart again”: Ritualizing consumerism in

sports on Weibo. International Journal of Sport Com-

munication, 6(3), 258–273.

Lombard, M., Snyder-Duch, J., & Bracken, C.C. (2002). Con-

tent analysis in mass communication: Assessment and

reporting of intercoder reliability. Human Communication

Research, 28(4), 587–604. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.

tb00826.x

Mahan, J.E., III. (2011). Examining the predictors of consumer

response to sport marketing via digital social media. Inter-

national Journal of Sport Management and Marketing,

9(3), 254–267.

Mahan, J.E., III, Seo, W.J., Jordan, J.S., & Funk, D. (2014).

Exploring the impact of social networking sites on running

involvement, running behavior, and social life satisfaction.

Sport Management Review; Advance online publication.

Mahoney, T.Q., Hambrick, M.E., Svensson, P.G., & Zimmer-

man, M.H. (2013). Examining emergent niche sports’

YouTube exposure through the lens of the psychological

continuum model. International Journal of Sport Man-

agement and Marketing, 13(3/4), 218–238. doi:10.1504/

IJsocial mediaM.2013.059717

Mangold, W.G., & Faulds, D.J. (2009). Social media: The new

hybrid element of the promotion mix. Business Horizons,

52(4), 357–365. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2009.03.002

McCarthy, B. (2014). A sports journalism of their own: An

investigation into the motivations, behaviours, and media

attitudes of fan sports bloggers. Communication & Sport,

2(1), 65–79. doi:10.1177/2167479512469943

Social Media Scholarship in Sport Management Research 615

JSM Vol. 29, No. 6, 2015

McEnnis, S. (2013). Raising our game: Effects of citizen jour-

nalism on Twitter for professional identity and working

practices of British sport journalists. International Journal

of Sport Communication, 6(4), 423–433.

McGillivray, D. (2014). Digital cultures, acceleration and mega

sporting event narratives. Leisure Studies, 33(1), 96–109.

doi:10.1080/02614367.2013.841747

McKelvey, S., & Masteralexis, J.T. (2013). New FTC guides

impact use of social media for companies and athlete

endorsers. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 22, 59–62.

McKelvey, S., & Masteralexis, J.T. (2011). This tweet sponsored

by . . . : The application of the new FTC guides to the social

media world of professional athletes. Virginia Sports and

Entertainment Law Journal, 11(1), 222–246.

McNary, E., & Hardin, M. (2013). Subjectivity in 140 charac-

ters: The use of social media by marginalised groups. In

P.M. Pedersen (Ed.), Routledge handbook of sport com-

munication (pp. 238–247). New York, NY: Routledge.

Miller, R., & Lammas, N. (2010). Social media and its impli-

cations for viral marketing. Asia Pacic Public Relations

Journal, 11, 1–9.

Miranda, F.J., Chamorro, A., Rubio, S., & Rodriguez, O.

(2014). Professional sports teams on social networks: A

comparative study employing the Facebook Assessment

Index. International Journal of Sport Communication,

7(1), 74–89. doi:10.1123/IJSC.2013-0097

Mumby, D.K., & Stohl, C. (1996). Disciplining orga-

nizational communication studies. Manage-

ment Communication Quarterly, 10(1), 50–72.

doi:10.1177/0893318996010001004

Neuendorf, K.A. (2002). The content analysis guidebook.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Norman, M. (2012). Saturday night’s alright for tweeting:

Cultural citizenship, collective discussion, and the new

media consumption/production of Hockey Day in Canada.

Sociology of Sport Journal, 29(3), 306–324.

O’Shea, M., & Alonso, A.D. (2011). Opportunity or obstacle?

A preliminary study of professional sport organisations

in the age of social media. International Journal of Sport

Management and Marketing, 10(3-4), 196–212.

O’Shea, M., & Alonso, A.D. (2013). Fan moderation of profes-

sional sports organisations’ social media content: Strategic

brilliance or pending disaster? International Journal of

Web Based Communities, 9(4), 554–570. doi:10.1504/

IJWBC.2013.057219

Pedersen, P.M. (2013). Reections on communication and sport:

On strategic communication and management. Communica-

tion and Sport, 1, 55–67. doi:10.1177/2167479512466655

Pedersen, P.M. (2014). A commentary on social media

research from the perspective of a sport communication

journal editor. Communication & Sport, 2(2), 138–142.

doi:10.1177/2167479514527428

Pegoraro, A. (2010). Look who’s talking—Athletes on Twitter:

A case study. International Journal of Sport Communica-

tion, 3(4), 501–514.

Pegoraro, A., & Jinnah, N. (2012). Tweet ’em and reap ’em: The

impact of professional athletes’ use of Twitter on current

and potential sponsorship opportunities. Journal of Brand

Strategy, 1(1), 85–97.

Phua, J. (2012). Use of social networking sites by sports

fans: Implications for the creation and maintenance of

social capital. Journal of Sports Media, 7(1), 109–132.

doi:10.1353/jsm.2012.0006

Pitts, B.G. (2001). Sport management at the millennium: A

dening moment. Journal of Sport Management, 15(1),

1–9.

Price, J., Farrington, N., & Hall, L. (2013). Changing the game?

The impact of Twitter on relationships between football

clubs, supporters and the sports media. Soccer & Society,

14(4), 446–461. doi:10.1080/14660970.2013.810431

Pronschinske, M., Groza, M.D., & Walker, M. (2012). Attract-

ing Facebook ‘fans’: The importance of authenticity and

engagement as a social networking strategy for profes-

sional sport teams. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 21(4),

221–231.

Reed, S. (2011). Sports journalists’ use of social media and its

effects on professionalism. Journal of Sports Media, 6(2),

43–64. doi:10.1353/jsm.2011.0007

Reed, S. (2013). American sports writers’ social media use and

its inuence on professionalism. Journalism Practice, 7(5),

555–571. doi:10.1080/17512786.2012.739325

Reed, S., & Hansen, K.A. (2013). Social media’s inuence on

American sport journalists’ perception of gatekeeping.

International Journal of Sport Communication, 6(4),

373–383.

Riegner, C. (2007). Word of mouth on the web: The impact

of Web 2.0 on consumer purchase decisions. Journal

of Advertising Research, 47(4), 436–447. doi:10.2501/

S0021849907070456

Rooney, D., McKenna, B., & Barker, J.R. (2011). History of