142

Journal of Sport Management, 2009, 23, 142-155

© 2009 Human Kinetics, Inc.

Off-Field Behavior of Athletes and Team

Identification: Using Social Identity Theory

and Balance Theory to Explain

Fan Reactions

Janet S. Fink

University of Connecticut

Heidi M. Parker

Syracuse University

Martin Brett

DeSales University

Julie Higgins

Mount St. Mary’s University

In the current article, we extend the literature on fan identication and social identity

theory by examining the effects of unscrupulous off-eld behaviors of athletes. In

doing so, we drew from both social identity theory and Heider’s balance theory to

hypothesize a signicant interaction between fan identication level and leadership

response on fans’ subsequent levels of identication. An experimental study was per-

formed and a 2 (high, low identication) 2 (weak, strong leadership response)

ANOVA was conducted with the pre to post difference score in team identication as

the dependent variable. There was a signicant interaction effect (F

(2, 80)

= 23.71, p <

.001) which explained 23% of the variance in the difference between prepost test

scores. The results provide evidence that unscrupulous acts by athletes off the eld of

play can impact levels of team identication, particularly for highly identied fans

exposed to a weak leadership response. The results are discussed relative to appropri-

ate theory. Practical implications and suggestions for future research are also for-

warded.

Team identication has captured the attention of sport researchers for a

number of years and relative to a variety of topics. Research regarding team iden-

tication has uncovered a variety of cognitive, affective, and behavioral outcomes

(Boyle & Magnusson, 2007; Kwon, Trail, & Anderson, 2005; Trail, Fink, &

Anderson, 2000; Wann & Grieve, 2005). Research has shown fans with high levels

Fink is with the University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269. Parker is with Syracuse University,

Syracuse, NY 13244. Brett is with DeSales University, Center Valley, PA 18034. Higgins is with

Mount St. Mary’s University, Emmittsburg, MD 21727.

MARKETING

Journal of Sport Management, 2009, 23, 142-155

© 2009 Human Kinetics, Inc.

Athlete Behavior and Team Identification 143

of team identication are more likely to attend games, pay more for tickets, buy

team sponsors’ products, and purchase more team merchandise (Madrigal, 1995;

Wakeeld, 1995; Wann & Branscombe, 1993). Wann and Branscombe (1993)

reported that fans higher in identication had higher expectations for team perfor-

mance while Madrigal (1995) found that fans higher in identication derived

more satisfaction from positive game outcomes. Perhaps most importantly, fans

high in identication are more likely to stay loyal to the team even when it is per-

forming poorly while less identied fans tend to engage in self-distancing tactics

(Wann & Branscombe, 1993).

Most of these studies, however, have dealt with fans’ reactions to on-eld

occurrences, that is, the play of the team. How athletes’ off-eld behavior impacts

fan identication is an under-studied area. At any given time of the year, allega-

tions of unscrupulous off-eld offenses by athletes are quite common. A recent

sampling includes professional baseball players accused of and admitting to ste-

roid use (Fainaru-Wada & Williams, 2003; Fox News, 2004); a professional foot-

ball team with nine players arrested in nine months (USA Today, 2007); and col-

lege football players accepting money from boosters (Dodd, 2006). These are just

a few examples which demonstrate that athletes are not immune from scandalous

acts. Thus, the question is posed, does this unscrupulous behavior impact fans’

identication with the team?

In the current article, we extend the literature on fan identication and social

identity theory by examining the effects of unscrupulous off-eld behaviors of

athletes. In doing so, we draw from both social identity theory and Heider’s bal-

ance theory to propose a specic hypothesis. We then test this hypothesis via an

experimental manipulation. Below we present the theoretical background sup-

porting the study’s hypothesis.

Conceptual Background and Hypothesis

Social Identity and Team Identification

Team identication stems from social identity theory. Social identity theory sug-

gests that individuals have both a personal identity and a social identity (Tajfel &

Turner, 1986). While the personal identity consists of distinctive attributes, such

as abilities and interests, social identity consists of signicant group categories

that can be based on demographic classications (e.g., sex, race) or organizational

membership (e.g., religious, educational, social institutions; Turner, 1982). When

a person identies with an organization, he or she observes, “a oneness with or

belongingness to the organization, where the individual denes him or herself in

terms of the organization(s) of which he or she is a member” (Mael & Ashforth,

1992, p. 104). Individuals are more likely to become identied with an organiza-

tion (or team) when it represents the attributes they assign to their own self-

concepts.

Social identity theory suggests that individuals are driven by a need for high

self-esteem and this self-esteem is established, in part, by being members of social

groups (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). People in groups make social comparisons in an

effort to enhance their self-esteem; they have favorable attitudes toward their own

group (in-group) and categorize other groups (outgroups) as inferior (Hogg &

Journal of Sport Management, 2009, 23, 142-155

© 2009 Human Kinetics, Inc.

144 Fink et al.

Abrams, 1999). Certainly this is true of sports fans. Highly identied fans are

more likely to show favoritism toward other fans of their team and criticize fans

of opposing teams (Branscombe & Wann, 1994; Wann & Branscombe, 1995;

Wann & Grieve, 2005). They see “their” team as an extension of themselves

(Wann, Melnkick, Russell, & Pease, 2001).

When presented with any sort of negative information regarding the group,

highly identied group members react differently than those with lower levels of

identication (Cohen & Garcia, 2005; Ellemers, Spears, & Doosje, 2002). Highly

identied members typically reafrm their group membership, while those with

lower levels of identication tend to distance themselves (Cohen & Garcia, 2005).

Such behaviors are apparent in sport fans. Wann and Branscombe (1990) found

that highly identied fans are less likely to distance themselves from the team

when the team lost than those who were less identied. Further, highly identied

fans exhibit biased attribution processing favoring their team (Wann & Dolan,

1994). That is, facing a win, highly identied fans ascribe the victory to internal

factors such as the skill of the team, or the coaching, and sometimes even fan sup-

port. However, upon a loss, rather than conceding another team’s superiority, they

blame the loss on more external factors such as fate or poor refereeing. Thus,

highly identied sports fans seem to undergo some sort of biased attributional

processes when dealing with a loss.

Team Identification and the Effects of Off-field Behavior:

In Group Bias and the Black Sheep Effect

However, losing on the eld of play is a natural aspect of sport. One team must

win, and one must lose. While not pleasant, sport fans must accept the fact that

sometimes their teams will lose. An athlete engaging in an unscrupulous act is

entirely different. These acts are not natural consequences of competition. Thus,

when a member of a team (i.e., an in-group member) engages in some sort of

immoral behavior, the fan must reconcile the positive feelings about the team with

the poor behavior of the athlete. This reconciliation may be different than when

facing a team loss. Dietz-Uhler, End, Demakakos, Dickirson, and Grantz (2002)

suggested that fans could react to these unscrupulous athletes in one of two ways,

either by exhibiting an in-group bias effect, or by exhibiting the “black sheep”

effect.

An in-group bias effect refers to the fact that group members often maintain

allegiance to the group, even when provided information that a group member has

failed (Dietz-Uhler, 1999). The failure of a group member is a threat to the group’s

identity, however, groups have numerous coping methods for reconciling the

action of the player with their views of the group. For example, fans might ques-

tion or degrade the reliability of the unattering information (e.g., the media is

“picking on” our team, the witnesses are not believable; Branscombe & Wann,

1994; Deitz-Uhler, 1999). They may accredit the “failure” to situational causes

(e.g., the athlete was in the wrong place at the wrong time) or engage in biased

attributions of the situation to put the group into a more positive light (e.g., the

athlete did not mean to do it, the athlete was merely protecting himself/herself;

Dietz-Uhler & Murrell, 1998; Wann & Dolan, 1994). The salient feature of these

coping mechanisms is sustained support for the group member committing the

unscrupulous act.

Journal of Sport Management, 2009, 23, 142-155

© 2009 Human Kinetics, Inc.

Athlete Behavior and Team Identification 145

On the other hand, the “black sheep” effect occurs when group members

derogate the guilty in-group member (athlete), and label him/her as “different”

than the rest of the group (Marques, Yzerbyt, & Leyens, 1988). This allows the

group members to maintain positive feelings about the group even in the wake of

an unscrupulous action of a group member because they no longer consider the

black sheep as representative of their group. Rather than supporting the guilty in-

group member, fans distance themselves from that particular member.

Dietz-Uhler et al. (2002) tested fans’ reactions to law breaking athletes who

were either a part of fans’ favorite teams, or a part of another team. Instead of

discovering a “black sheep” effect, they found an in-group bias effect in that par-

ticipants evaluated the law-breaking athlete from their favorite team more highly

than the athlete from a rival team, even when the rival athlete had not engaged in

criminal behavior. However, the study did not measure team identication, thus

the effects of identication on these reactions could not be ascertained. As the

authors noted (2002, p. 168), “the possibility exists that these subjects were not

highly identied with their favorite football team.” Certainly one can have a favor-

ite team, yet not be highly identied. Further, their study focused on participants’

attitudes toward the law-breaking athlete, while the current study focuses on atti-

tudes toward the team when an athlete on the team engages in an unscrupulous

act.

When examining feelings about the team in the wake of an unscrupulous act

by a player, either the in-group bias response, or the “black sheep” effect should

allow the fan to maintain their allegiance to the team. Either of these two broad

mechanisms can allow fans to feel good about their team when faced with the

negative information regarding a particular player. Whether the fan throws greater

support behind the player (in-group bias), or creates distance from the player

through derogation tactics (“black sheep” effect), such responses serve to allow

for reconciliation between the unscrupulous act of a group member, and the posi-

tive feelings about the group. However, identication with the group plays a key

role. Highly identied group members are much more likely to exhibit coping

reactions when their group is threatened (Branscombe & Wann, 1994, Branscombe,

Wann, Noel, & Coleman, 1993). Because highly identied fans see the team as a

reection of themselves, they will experience a greater need to reconcile the act

through some sort of coping mechanism.

Leadership Response: The Effect of Balance Theory on Fans’

Responses

In addition, the response of team leaders should impact fans’ responses to an off-

eld incident. Balance theory purports that individuals strive to maintain a sense

of balance in their lives (Heider, 1958). They attempt to reach “a harmonious

state, one in which the entities comprising the situation and the feelings about

them t together without stress” (Heider, 1958, p. 180). An individual’s need to

reconcile feelings toward the immoral player behavior with his/her feelings toward

the group as a whole leads to this imbalanced state, with positive feelings regard-

ing the team, yet negative feelings regarding a team member. Therefore, some-

thing must be done to “balance” the situation. Left to their own devices, fans

could engage in one of many balancing techniques (e.g., distancing oneself from

the team, derogating the in-group member, exhibiting in-group bias) depending

Journal of Sport Management, 2009, 23, 142-155

© 2009 Human Kinetics, Inc.

146 Fink et al.

upon their level of identication. However, different leadership responses to the

unscrupulous act should present different reactions.

A rm and swift response from the head coach, athletic director, or owner

(i.e., management) should allow for greater “balance” in the participant’s mind.

That is, if the participant feels that team leaders are also affronted by the incident,

and a “punishment” that ts the incident is levied, he/she might feel better about

the team as a whole because the unscrupulous player can be seen as an anomaly

and somehow “different” from the rest of the team. This response, in fact, could

activate the “black sheep” effect. Group members can still feel good about their

team, because their team still espouses the values they hold dear—the coach

makes it clear the action by the athlete is not representative of the group.

However, would fans’ attitudes differ if team leaders knew about the impro-

priety and did nothing about it, or attempted to “protect” the unscrupulous ath-

lete? If the team’s response is such, there is no longer a black sheep to blame.

With leadership failing to denounce the act, suddenly the whole team can be

viewed in an undesirable light. Then, it becomes quite difcult for a person con-

nected with the team to maintain a balance. Given this response, fans may feel that

the team (group) itself no longer espouses the values that they hold dear, and the

team is less of a reection of their personal identities. Thus, he/she may begin to

disidentify with the team.

Considering social identity theory and the balance theory in tandem, one

would expect that an individual with stronger ties to an organization would have a

greater need to obtain “balance” when something negative occurs within the orga-

nization. Indeed, Dietz-Uhler (1999) found that highly identied group members

were more likely to engage in biased processing of negative group information to

maintain a more positive social identity. Because the highly identied individual

expresses a “oneness” with the organization, he/she especially will need some-

thing positive to counteract the negative situation. Highly identied fans should

feel more compelled to seek out positive information to counteract the negative.

Doosje, Branscombe, Spears, and Manstead (1998) noted that when presented

with both negative and positive information about a group, highly identied mem-

bers placed more emphasis on the positive information to maintain a favorable

feeling about their connectedness to a group. Thus, highly identied fans should

be more inuenced by leadership’s response to a negative situation than those less

identied—that is, they, especially, will look for something positive to maintain

the balance of being connected to the group which they love when faced with

unscrupulous actions of a group member (i.e., player). If these highly identied

fans perceive that team leaders do not condone the action, these fans may have

negative feelings about the individual athlete, but their feelings about the team

should remain positive.

The above background literature leads to the hypothesis of this study.

H1: There will be a signicant interaction between fan identication level

and leadership response on fans’ subsequent levels of identication. When

highly identied fans are faced with information regarding an unscrupulous

act by a team player, their team identication will change as a function of

leadership’s response to the situation.

Journal of Sport Management, 2009, 23, 142-155

© 2009 Human Kinetics, Inc.

Athlete Behavior and Team Identification 147

Method

Procedures and Participants

We incorporated a 2 (high vs. low identication) 2 (strong vs. weak leadership

response) analysis of variance (ANOVA) to test the hypothesis. Participants’

change in team identication scores (pre–post) served as the dependent variable.

First, participants were pretested on their initial levels of fan identication

which was used to create high and low identied groups. Two weeks later, partici-

pants received one of two newspaper story manipulations creating four groups:

high fan identication-strong leadership response (n = 23); high fan identica-

tion-weak leadership response (n = 20); low fan identication-strong leadership

response (n = 20); and low fan identication-weak leadership response (n = 19).

Manipulation

Copies of a life-like newspaper article were designed for the study. The “article”

was constructed to look exactly like one taken from the local newspaper’s web-

page. It had the newspaper’s insignia, a current sportswriter’s byline, and the

“breaking news” headlines aspect found in the actual newspaper Web page.

The newspaper story described the university’s star quarterback charged with

serious off-eld offenses, drunk and disorderly conduct and assault and battery. In

the “strong leadership response” manipulation, the coach and athletic director

responded to the charges quickly, expressed severe disappointment in the behav-

ior of the athlete, indicated the behavior was not consistent with their expectations

for team member behavior, and immediately suspended the player from the team.

In the “weak leadership response” manipulation, the coach and athletic director

were slow to respond to the charges, indicated that the pending offenses were a

“team matter” and would be dealt with internally, and punishment, if given, would

be administered after all the facts had been gathered.

Study participants were undergraduate students who were enrolled in human-

ities classes (N = 88) at a Midwestern university. Humanities classes were used to

obtain more variability in team identication. The study was conducted during

class time and participation was voluntary. Participants were given a brief intro-

duction of the study by the experimenters, in which they were told that they were

being used as part of a sport marketing study. All students were told to put a code

name on their survey and were rst pretested on the fan identication scale. The

experimenters used the pretest scores to group subjects into high (M = 5.93) or

low (M = 2.99) identication categories using a conceptual split. Because 4 was

the midpoint on the scale, those below a 4.00 were considered “low” while those

5.00 or above were considered “high.” This resulted in the loss of six original

subjects. Results of an independent sample t test indicated that the group means

were signicantly different (t

(1, 81)

= 1.76, p < .001) for the high and low groups.

Using the code names, participants were randomly assigned to the strong/weak

manipulations, ensuring near equal numbers of the manipulations between the

high/low participants.

Three weeks later, the experimenters handed out the materials (the one-page

newspaper article and the subsequent page with manipulation check and posttest

Journal of Sport Management, 2009, 23, 142-155

© 2009 Human Kinetics, Inc.

148 Fink et al.

measure) using the code names. Participants were told that they were being tested

that day due to the breaking news that was contained in the newspaper article.

Participants had two minutes read the article. They then completed the post test

team identication measure and, after that, the manipulation check measure. After

all participants had completed the materials, the class was debriefed and told that

the newspaper story was made up and the content was not true.

Measures

The mean of the items represented the nal score for each measure. Reliability

estimates (Cronbach’s alpha) were calculated for each measure and are reported

below.

Fan identication was tested using Trail and James’ (2001) 3-item Team

Identication Index (TII) which utilizes a 7-point Likert scale. An example item

is: “I consider myself a big fan of the ________________”(university team mascot

name). Individual items were totaled and divided by the number of items to obtain

a mean score. The reliability estimate was high ( = .87).

Leadership response was measured to ensure that the manipulation was suc-

cessful. Three items made up the scale and were preceded by the phrase, “the

athletic department’s response to this situation was . . .” and anchored by 7-point

semantic differential scales. The endpoints were “weak-strong,” “lenient-strict”

and “moderate-rm.” Individual items were totaled and divided by the number of

items to obtain a mean score. The reliability estimate for the measure was high (

= .91)

Analyses

A 2 (high vs. low identication) 2 (strong vs. weak leadership response) analy-

sis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test the hypothesis. Participant’s change in

identication scores on the team identication measure (pre–post) served as the

dependent variable.

Results

Manipulation Check

To ensure that the manipulation was successful, an independent sample t test was

performed. The means of the two conditions within the manipulation (i.e., strong

versus weak leadership response) were signicantly different, t

(1,81)

= 7.38, p <

.001. The mean for the “weak leadership response” condition was 1.7 (SD = .81)

while the mean for the “strong leadership response” condition was 5.3 (SD = 1.4).

Thus, the manipulation was successful.

Hypothesis Testing

To test the hypothesis, a difference score was calculated by taking a subject’s

pretest mean score and subtracting it from the subject’s posttest mean score on the

team identication scale. Then a 2 (high, low identication) 2 (weak, strong

Journal of Sport Management, 2009, 23, 142-155

© 2009 Human Kinetics, Inc.

Athlete Behavior and Team Identification 149

leadership response) ANOVA was conducted with the difference score as the

dependent variable. There was a signicant interaction effect (F

(2, 80)

= 23.71, p <

.001) which explained 23% of the variance in the difference between prepost test

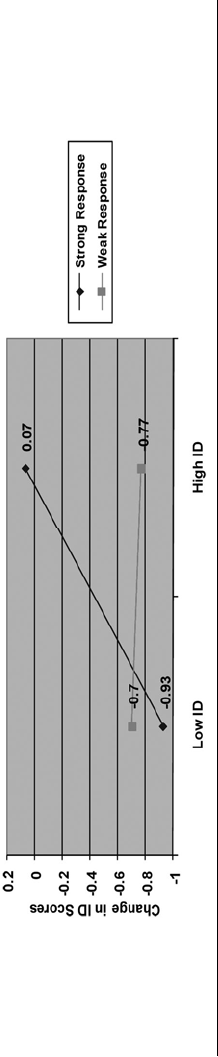

scores. As Figure 1 and Table 1 indicate, fans low in team identication showed

very little difference in their pre and post test scores as a result of the manipulation

regardless of the managerial response. However, in the high identication group,

those exposed to the weak leadership response showed a signicant decrease in

their identication scores (mean difference score = –.76) while scores for those

exposed to the strong leadership response remained relatively stable (mean differ-

ence score = .07). Further, a one sample t test against zero indicated that the

decrease in identication scores for this group was signicant (t = 9.89, p < .001)

while the changes in the other groups were not signicantly different from zero.

Discussion

The results of this study provide evidence that unscrupulous acts by athletes off

the eld of play can impact levels of team identication. This was particularly true

for highly identied fans exposed to the “weak leadership response.” The ANOVA

revealed that those fans, compared with the others, experienced a decrease in their

fan identication scores. This supports the notion that social identity theory can

work in tandem with the balance theory. People who are highly identied fans

have a greater need to achieve balance when presented with an in-group member

(athlete) who commits an unscrupulous act. When team leaders actually support

that athlete, it appears that the fan has nothing “positive” to attach him or herself

to–thus, their fan identication scores drop. However, when team leaders pro-

vided a strong response, one that clearly denoted the athlete’s actions were out of

line with team expectations for behavior, it provided something positive for the

highly identied fan to attach to in the wake of outsiders’ negative commentary

regarding the situation. Thus, the “threat” to the team’s social status was miti-

gated. Most likely this was the result of a “black sheep” effect. Highly identied

subjects in the “strong leadership response group” could more easily consider the

athlete on their team as an anomaly, acting inconsistently with the team (group)

values with which the fan feels a connection. This is, in fact, consistent with

others’ work. Branscombe et al. (1993) showed that the most highly identied

group members responded most negatively to in-group members who failed to

live up to the positive group image. If the highest identiers automatically have a

tendency to engage in the black sheep coping mechanism, that mechanism could

certainly be enhanced with the “strong leadership response.”

Social groups structure a foundation for identity and the concepts of our per-

sonal identities intersect with our social group memberships (Tajfel & Turner,

1986). Therefore, it is not surprising that the behavior of in-group members was

germane to subjects’ team identity scores. Recent work in social psychology has

elucidated the concept of “vicarious shame” (Lickel, Schmader, Curtis, Scarnier,

& Ames, 2005). This work has shown that people can feel ashamed of a negative

event, even if they are not personally responsible for it. Just as fans can experience

vicarious achievement with a successful other even though they personally con-

tributed nothing to the victory (Cialdini, Borden, Thorne, Walker, Freeman, &

Journal of Sport Management, 2009, 23, 142-155

© 2009 Human Kinetics, Inc.

150

Figure 1 — Graph of interaction effect: pretest, posttest difference scores.

Journal of Sport Management, 2009, 23, 142-155

© 2009 Human Kinetics, Inc.

Athlete Behavior and Team Identification 151

Sloan, 1976), it seems that people are capable of experiencing shame even if they

had nothing to do with the wrongdoing (Johns, Schmader, & Lickel, 2005). How-

ever, this vicarious shame is predicated on identication with the group. As Lickel

et al. (2005, p. 148) stated:

Because perceptions of a shared social identity are a source of self-identi-

cation and esteem, people are invested in maintaining a positive reputation of

their social identities and are loath to have negative stereotypes about their

groups conrmed.

When faced with a negative action by an ingroup member, Lickel et al. (2005)

found that people felt vicarious shame when they had a strong shared social iden-

tity with the wrongdoer, and thus felt that this negative event would somehow

reect badly on them personally. In addition, they found that this sense of shame

led people to distance themselves from the wrongdoer and the event.

Though we did not directly measure shame, it is plausible that because of

highly identied fans’ strong connections with the team, they felt vicarious shame

for the athlete’s wrongdoing. Indeed, a quick perusal of recent sport incidents in

which players have engaged in unscrupulous acts hint at these feelings. For exam-

ple, after the eighth athlete from the Cincinnati Bengal was arrested in 2006,

coach Marvin Lewis said, “It’s an embarrassment to our organization, to our city,

and to our fans” (Maske & Carpenter, 2006). A blogger was even more insistent.

He wrote:

I am utterly ashamed and appalled to be a fan of the Cincinnati Bengals. I

have spent the last 17 years of my life as a fan of the Bengals, not much by

most people’s standards, but quite a lot considering I’m only 22 years old. . .

. Until I see changes in the drafting and team-building policies of the Cincin-

nati Bengals franchise, I will no longer be a fan. I can tolerate losing with

dignity, and certainly winning with class, but I cannot handle winning with

criminals. Until further notice, I will no longer be wearing my orange and

black. (Brown, 2006)

An NBA enthusiast had this to say following the ugly brawl that occurred

between fans and players in the Detroit Pistons-Indiana Pacers game:

Being a sports fan carries with it the potential for both immense joy and dis-

appointment. There’s the thrill of watching the players you emulate succeed

against bitter rivals. There’s the dejection that accompanies painful losses.

Table 1 Means and Standard Deviations: Difference Scores

High-Low Id Group Managerial Response Group M SD N

Low id weak –.7016 .56641 19

strong –.9333 .70636 20

High id weak –.7668 .34331 20

strong .0729 .28321 23

Dependent variable: Difference scores

Journal of Sport Management, 2009, 23, 142-155

© 2009 Human Kinetics, Inc.

152 Fink et al.

And this week I have just discovered a third emotion—shame. Not shame at

outcomes, but shame at the way the team I support and the fans I identify with

act on the eld. (Mata-Fink, 2004)

Thus, it does appear that some fans are capable of feeling vicarious shame

when a team member is caught committing an immoral act.

Implications, Future Directions, and Limitations

The results of this study suggest that unscrupulous acts by athletes can affect

highly identied fans’ level of identication with the team. Further, the response

by team leaders appears to be vital in mitigating those effects. The implication is

clear. Team leaders (e.g., coaches, athletic directors, management) must carefully

plan their response to unscrupulous off-eld acts. When an athlete has clearly

engaged in a devious act, team leaders should denounce the act as inconsistent

with the team’s expectations for behavior as this appears to lessen the negative

impact of the act. Failure to respond in such a manner could serve to dispirit the

general public as well as their core base of highly identied fans.

Future research should attempt to measure the longitudinal effects of such

dubious acts. A limitation of this study is that posttest measures of fan identica-

tion were collected immediately after subjects read the mock newspaper article. It

is plausible that fans experience an immediate reaction that subsides after time.

This is a particularly important point given the fact that most studies on identica-

tion show it to be a relatively stable trait, especially for those who are highly

identied (Cialdini et al., 1976; Wann & Branscombe, 1990).

The experimental nature of the study prohibited such longitudinal measure-

ment as subjects had to be deceived into thinking the mock newspaper article was

genuine, then debriefed regarding the true nature of the study upon completion of

the post test measure. Had subjects been given another post test measure some

time later, they would have known the story regarding the athlete was not true.

Similarly, future studies should assess the impact of a series of off-eld inci-

dents by athletes on the same team. For example, perhaps the Bengal’s fan quoted

above did not feel such shame after the rst incident, but reached that point after

a certain number of incidents. It may be easier to explain away one dubious act,

but much more difcult to feel a sense of connection with the team when such acts

occur frequently. Further, future studies should attempt to measure vicarious

shame to concretely determine whether fans feel such emotions in the aftermath

of such events.

Future studies should also assess reactions of fans of different teams. Some

teams have historically embraced and espoused a rogue image (e.g., Miami Hur-

ricanes, Oakland Raiders). Highly identied fans of these types of teams may

connect to the team because of such qualities. If so, they would be much less

likely to distance themselves from the team (or the athlete) in the wake of scandal-

ous behavior.

In addition, future studies should incorporate fans’ point of attachment.

Recent research has shown that the object of a fan’s identication can stem from

numerous aspects: the team itself, particular players, the coach, the organization,

and even the community in which the organization plays (Kwon, Trail, &

Journal of Sport Management, 2009, 23, 142-155

© 2009 Human Kinetics, Inc.

Athlete Behavior and Team Identification 153

Anderson, 2005; Trail, Robinson, Dick, & Gillentine, 2003). Results may differ if

the fan’s point of attachment is high for the particular player that causes the trouble

and relatively low, in comparison, to the team itself. If a fan’s attachment is solely

to a player, it stands to reason that he/she will not view the organization or its

leaders as part of the “in-group.” Subsequently, fans may react differently relative

to the object of their attachment.

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that sport fans are not immune

to the unscrupulous off-eld acts of athletes. In fact, such acts have a negative

impact on team identication levels, particularly when the response by team lead-

ers was perceived to be weak and lenient. This is especially true for those with the

highest levels of team identication. Further, the results suggest that aspects of

social identity theory and the balance theory are inuential in predicting and

explaining fan response to such events.

References

Boyle, B.A., & Magnusson, P. (2007). Social identity and brand equity formation: A com-

parative study of collegiate sports fans. Journal of Sport Management, 21, 497–520.

Branscombe, N.R., & Wann, D.L. (1994). Collective self-esteem consequences of out-

group derogation when a valued social identity is on trial. European Journal of Social

Psychology, 24, 641–657.

Branscombe, N.R., Wann, D.L., Noel, J.G., & Coleman, J. (1993). In-group or out-group

extremity: Importance of the threatened social identity. Personality and Social Psy-

chology Bulletin, 19, 381–388.

Brown, L. (2006, July 16). Ashamed to be a Bengals fan. Larry Brown’s commentaries.

Fox Sports. Retrieved February 8, 2007, from http://community.foxsports.com/blogs/

larrybrownsports/2006/07/14/Ashamed_to_be_a_Bengals_Fan

Cialdini, R.B., Borden, R.J., Thorne, A., Walker, M.R., Freeman, S., & Sloan, L.R. (1976).

Basking in reected glory: Three (football) eld studies. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 34, 366–375.

Cohen, G.L., & Garcia, J. (2005). I am us: Negative stereotypes as collective threats. Jour-

nal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 566–582.

Dietz-Uhler, B. (1999). Defensive reactions to group relevant information. Group Pro-

cesses & Intergroup Relations, 2, 17–29.

Deitz-Uhler, B., End, C., Demakakos, N., Dickirson, A., & Grantz, A. (2002). Fans’ reac-

tions to law breaking athletes. International Sports Journal, 6, 160–170.

Dietz-Uhler, B., & Murrell, A. (1998). The effects of social identity and threat on self-

esteem and attributions. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, &. Practice, 2, 24–35.

Dodd, D. (2006, August 3). Sorting out the mess in Norman. Not a moment too soon. CBS

SportsLine. Retrieved February 1, 2007, from http://cbs.sportsline.com/collegefoot-

ball/story/9584077

Doosje, B., Branscombe, N.R., Spears, R., & Manstead, A.S.R. (1998). Guilty by asso-

ciation: When one’s group has a negative history. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 75, 872–886.

Ellemers, N., Spears, R., & Doosje, B. (2002). Self and social identity. Annual Review of

Psychology, 53, 161–186.

Fainaru-Wada, M., & Williams, L. (2003, December 25). Barry Bonds: Anatomy of a scan-

dal. Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved November 22, 2006, from http://seattlepi.

nwsource.com/baseball/153951_steriods25.html

Journal of Sport Management, 2009, 23, 142-155

© 2009 Human Kinetics, Inc.

154 Fink et al.

Fox News. (2004, December 2). Giambi told jury he used steroids. Fox News. Retrieved

November 22, 2006, from http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,140245,00.html

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: John Wiley and

Sons.

Hogg, M.A., & Abrams, D. (1999). Social identity and social cognition: Historical back-

ground and current trends. In D. Abrams & M.A. Hogg (Eds.), Social identity and

social cognition (pp. 1–25). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Johns, M., Schmader, T., & Lickel, B. (2005). Ashamed to be an American? The role of

identication in predicting vicarious shame for anti-Arab prejudice after 9-11. Self

and Identity, 4, 331–348.

Kwon, H., Trail, G., & Anderson, D. (2005). Are multiple points of attachment necessary

to predict cognitive, affective, conative, or behavioral loyalty? Sport Management

Review, 8, 225–270.

Lickel, B., Schmader, T., Curtis, M., Scarnier, M., & Ames, D.R. (2005). Vicarious shame

and guilt. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 8, 145–157.

Madrigal, R. (1995). Cognitive and affective determinants of fan satisfaction with sporting

event attendance. Journal of Leisure Research, 27, 205–227.

Mael, F., & Ashforth, B.E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater. A partial test of the refor-

mulated model of organizational identication. Journal of Organizational Behavior,

13, 103–123.

Marques, J.M., Yzerbyt, V.Y., & Leyens, J.P. (1988). The black sheep effect? Extremity of

judgments toward ingroup members as a function of group identication. European

Journal of Social Psychology, 18, 1–16.

Maske, M., & Carpenter, L. (2006, December 16). Player arrests put the NFL in a defensive

mode. The Washington Post. Retrieved February 15, from http://www.washington-

post.com/wpdyn/content/article/2006/12/15/AR2006121502134.html

Mata-Fink, J. (2005, April 19). The pantheon of casual sports. The Stanford Daily.

Retrieved February 15, from http://daily.stanford.edu/article/2005/4/19/thePantheon-

OfCasualSports

Taijfel, H., & Turner, J.C. (1986). Social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In W.

Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (2nd ed., pp. 33–47).

Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

Trail, G.T., Fink, J.S., & Anderson, D. (2000). A comprehensive model of sport consumer

behavior. International Journal of Sport Management, 1(3), 154–180.

Trail, G.T., & James, J. (2001). The motivation scale for sport consumption. Assessment of

the scale’s psychometric properties. Journal of Sport Behavior, 24, 108–127.

Trail, G.T., Robinson, M.J., Dick, R.J., & Gillentine, A.J. (2003). Motives and points of

attachment: Fans versus spectators in intercollegiate athletics. Sport Marketing Quar-

terly, 12(4), 217–227.

Turner, J.C. (1982). Towards a cognitive redenition of the social group. In H. Taijfel (Ed.),

Self, Identity, and Intergroup Relations (pp. 15–40). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press.

Today, U.S.A. (2007, January 22). Bengals Joseph arrested for marijuana possession. USA

Today. Retrieved February 1, 2007, from http://www.usatoday.com/sports/football/

n/bengals/2007-01-22-joseph-arrest_x.htm.

Wakeeld, K.L. (1995). The pervasive effects of social inuence on sporting event atten-

dance. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 19, 335–351.

Wann, D.L., & Branscombe, N.R. (1990). Die-hard and fair-weather fans: Effects of iden-

tication on BIRGing and CORFing tendencies. Journal of Sport and Social Issues,

14, 103–117.

Wann, D.L., & Branscombe, N.R. (1993). Sports fans: Measuring degree of identication

with their team. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 24, 1–17.

Journal of Sport Management, 2009, 23, 142-155

© 2009 Human Kinetics, Inc.

Athlete Behavior and Team Identification 155

Wann, D.L., & Branscombe, N.R. (1995). Inuence of identication with a sports team on

objective knowledge and subjective beliefs. International Journal of Sport Psychol-

ogy, 26, 551–567.

Wann, D.L., & Dolan, T.J. (1994). Attributions of highly identied sports spectators. The

Journal of Social Psychology, 134, 783–792.

Wann, D.L., & Grieve, F.G. (2005). Biased evaluations of in-group and out-group spectator

behavior at sporting events: The importance of team identication and threats to social

identity. The Journal of Social Psychology, 145, 531–545.

Wann, D.L., Melnick, M.J., Russell, G.W., & Pease, D.G. (2001). Sport fans: The psychol-

ogy and social impact of spectators. New York: Routledge.

Journal of Sport Management, 2009, 23, 142-155

© 2009 Human Kinetics, Inc.